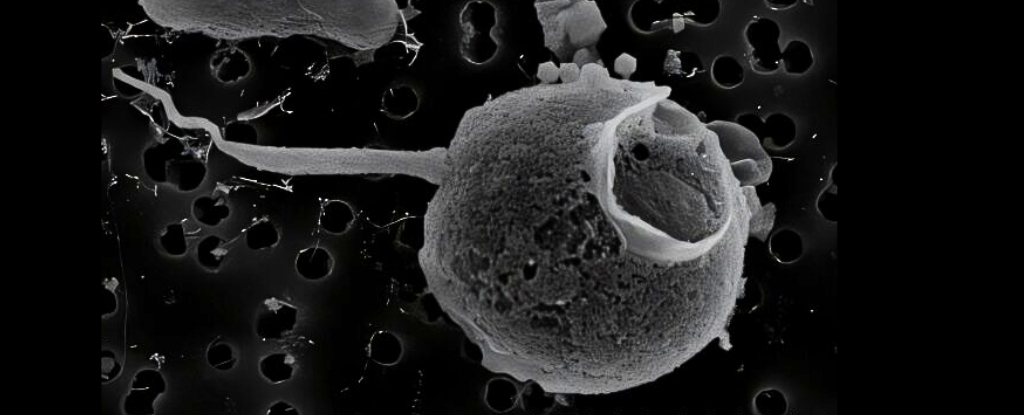

A remarkable discovery in the Pacific Ocean has revealed a viral particle with the longest tail ever recorded on a virus. The virus, named PelV-1, was found infecting dinoflagellate plankton, specifically targeting species of the Pelagodinium genus. This unprecedented tail, which measures approximately 2.3 micrometers, not only aids in attaching the virus to its host but may also assist in locating these plankton, which are often sparsely distributed in the vast upper layers of the ocean.

Research led by Andrian Gajigan, an oceanographer at Cornell University, highlights that while most virus tails are measured in nanometers, PelV-1’s tail exceeds the length of previously recorded viral tails. To put this into perspective, the tail of the longest known phage, P74-26, measures around 875 nanometers, while another giant virus, Tupanvirus, has tails ranging from 0.55 to 1.85 micrometers. The research team notes that despite the significant difference in tail length, the ratio of PelV-1’s tail to its head remains consistent with that of P74-26, leaving questions about the potential biological mechanisms behind this ratio.

Understanding the Role of Viruses in Marine Ecosystems

Since their initial discovery in 2003, giant viruses have continued to surprise scientists with their complexities. Some of these viruses are larger than bacteria and have provided insights into cellular structures, blurring the lines between living organisms and inanimate entities. Despite their significance, the role of viruses in the ecology of dinoflagellates—key players in Earth’s oxygen production and nutrient cycling—remains largely unexplored.

Dinoflagellates are integral to marine ecosystems, contributing not only to oxygen generation but also cycling nutrients, including carbon. However, they can also trigger harmful algal blooms that impact waterways and the organisms that depend on them, including fisheries and wildlife. As Gajigan and his team point out, “how viruses influence dinoflagellate ecology remains little known.”

The research findings, which have been made publicly available on bioRxiv prior to peer review, underscore the need for further exploration into the interactions between viruses and plankton. Given that very few viruses have been isolated from plankton so far, the scientific community anticipates that many more discoveries await.

As scientists continue to study these giant viruses, they may uncover crucial information about their ecological roles and the potential effects on marine environments. Understanding these dynamics is essential, especially as human activities increasingly impact ocean health and biodiversity.