A team of researchers from the Mayo Clinic has made a breakthrough in the fight against type 1 diabetes by demonstrating how a protective layer of sugar molecules can shield pancreatic tissue from immune system attacks. This innovative approach was tested using female mice genetically predisposed to develop the mouse version of type 1 diabetes.

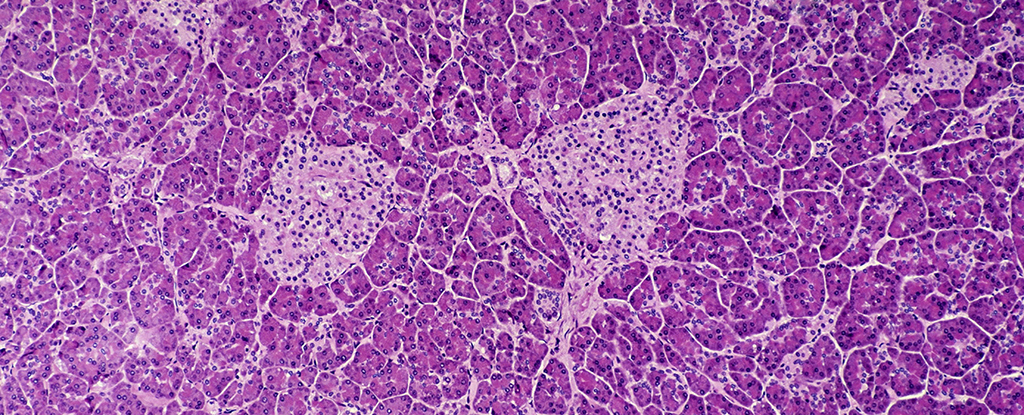

In the study, a group of genetically engineered mice produced higher levels of an enzyme known as ST8Sia6 in their pancreatic beta cells. This enzyme facilitated the coating of beta cells with a type of sugar called sialic acid. These beta cells are critical for insulin production and blood sugar regulation. In individuals with type 1 diabetes, the immune system mistakenly targets and destroys these cells.

The results were striking. In the untreated control group, 60 percent of the mice developed type 1 diabetes, while only 6 percent of the mice with the sialic acid coating experienced the same fate. This represents a remarkable 90 percent reduction in the disease’s onset among the treated group.

“Our findings show that it’s possible to engineer beta cells that do not prompt an immune response,” stated immunologist Virginia Shapiro. The discovery of this sugar-coating mechanism emerged during cancer research, where tumor cells were found to utilize the same enzyme and sugar to evade immune destruction. This protective layer acts almost like a signal to the immune system, indicating that these beta cells should be preserved.

Remarkably, the immune system of the treated mice remained functional and intact. “Though the beta cells were spared, the immune system remained intact,” explained medical researcher Justin Choe. “We found that the enzyme specifically generated tolerance against autoimmune rejection of the beta cell, providing local and quite specific protection against type 1 diabetes.”

While these findings are promising, they come with the typical caution associated with preclinical trials. The effectiveness of this approach in humans remains to be seen. Researchers acknowledge that one of the main challenges in curing type 1 diabetes is the unclear understanding of its triggers. It is believed that a combination of genetic and environmental factors may contribute to the autoimmune response that destroys beta cells.

Type 1 diabetes affects millions of people worldwide, requiring continuous monitoring of blood sugar levels and daily insulin administration through injections or pumps to prevent serious health complications.

Shapiro emphasized the potential future implications of this research: “A goal would be to provide transplantable cells without the need for immunosuppression. Though we’re still in the early stages, this study may be one step toward improving care.”

The results of this study have been published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, highlighting the ongoing efforts to find innovative solutions for type 1 diabetes and improve the lives of those affected by the condition.