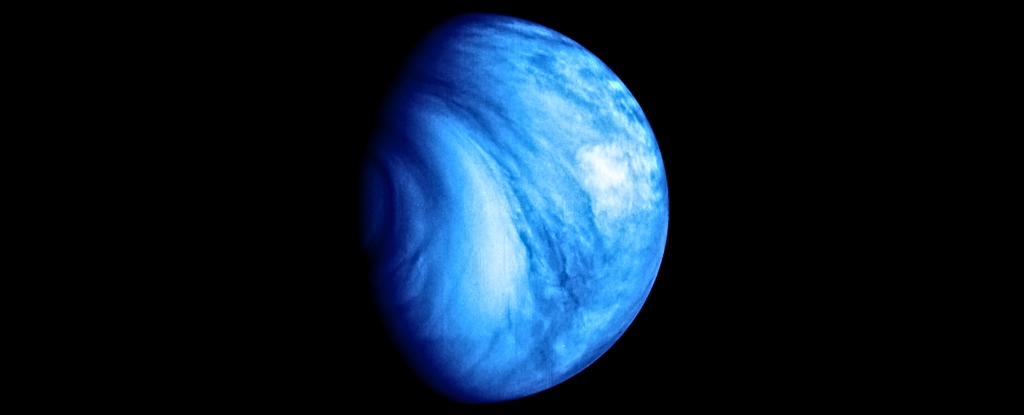

A recent analysis of data from the 1970s has confirmed that the clouds of Venus are primarily composed of water, rather than the previously assumed sulphuric acid. This revelation, published in the journal *Nature Astronomy* on October 16, 2023, changes the understanding of the planet’s atmospheric conditions and hints at the possibility of liquid water existing in its clouds.

Scientists from the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA re-evaluated data collected from the **Pioneer Venus** and **Magellan** missions. Their findings indicate that water vapour constitutes about **70%** of the clouds surrounding Venus, a significant departure from earlier models that suggested a more acidic composition. This new insight raises intriguing questions about the planet’s climate and its potential for hosting life.

Historical Context and Data Reassessment

The initial data collection took place during the **1970s**, when the Pioneer spacecraft sent back crucial information about Venus’s atmosphere. For decades, researchers believed that the thick, acidic clouds were primarily made of sulphuric acid droplets. However, recent advances in analysis techniques prompted a closer look at the existing data.

According to the lead researcher, Dr. **Nina L. V. van der Voet** from the Netherlands Institute for Space Research, the study was driven by a desire to reassess the fundamental assumptions about Venus’s atmosphere. “We were surprised to find such a high percentage of water in the clouds. It challenges what we thought we knew about our closest planetary neighbour,” Dr. van der Voet explained.

The researchers utilized spectroscopic data to measure the infrared light reflected by the planet’s clouds. This method enabled them to determine the composition with greater accuracy than previous analysis methods.

Implications for Future Exploration

The new understanding of Venus’s clouds opens up avenues for further exploration. Scientists are particularly interested in the implications for astrobiology, as the presence of water vapour could suggest that conditions might have been suitable for life in the past.

Venus’s extreme surface conditions, with temperatures reaching **467 degrees Celsius** and atmospheric pressure about **92 times** that of Earth’s, make it an inhospitable environment. Yet, understanding the atmospheric processes at play could inform future missions aimed at exploring the planet’s potential for life.

NASA and ESA have plans to send missions to Venus within the next decade. The **DAVINCI+** and **VERITAS** missions are slated for launch in the early **2030s**, focusing on the planet’s atmosphere and geological history. The findings from this recent study will likely influence mission objectives, particularly regarding the search for signs of past life.

As researchers continue to examine the implications of these findings, the question remains: how did scientists overlook such a significant detail about Venus’s atmosphere for so many years? The answers may lie in the challenges of interpreting complex data and the limitations of earlier technology.

This new perspective on Venus not only enhances our understanding of the planet itself but also underscores the importance of revisiting and re-evaluating historical data with modern tools. As exploration of our solar system advances, the knowledge gained from Venus may inform broader questions about the potential for life beyond Earth.