A recent study led by the University of Washington reveals that while the Paris Agreement has fostered some reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, these efforts have not been sufficient to offset the rising emissions tied to global economic growth. Signed by nearly 200 nations a decade ago, the agreement aimed to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, ideally capping it at 1.5 degrees.

The study, published on October 17, 2023, analyzed emissions data from the past decade, highlighting that, despite some progress, the net impact remains detrimental. As Adrian Raftery, a professor emeritus of statistics and sociology at the University of Washington, noted, “The efforts made in response to the Paris Agreement did change the course of things, but the effects were knocked out by an increase in gross domestic product.”

Progress and Challenges in Emission Reductions

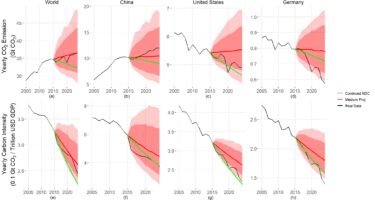

The research indicates that while carbon intensity—the measure of carbon emissions per dollar of economic output—has improved, total emissions have continued to rise. The annual reduction in carbon intensity has increased to 3.1%, up from 1.1% prior to the agreement. Yet, this progress is overshadowed by significant GDP growth. As Raftery explained, “Even though less carbon was released to produce each economic unit, global GDP increased enough to drive total emissions up.”

This study marks the third in a series from Raftery and his colleagues. Their initial findings in 2017 suggested that even if all countries met their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), there was only a 5% chance of keeping warming below the critical 2-degree Celsius mark. A follow-up in 2021 indicated that emissions goals would need to be 80% more ambitious to achieve the desired climate outcomes.

The current research applies updated statistical methods to assess the last decade’s data, reflecting the complexities of achieving climate goals. Although the chance of severe climate change scenarios has decreased from 26% to 9% since the agreement’s adoption, the likelihood of limiting warming to below 2 degrees has only risen to 17%.

Global Emissions Trends and Key Contributors

The study underscores the disproportionate impact of larger economies on global emissions. China, responsible for nearly one-third of the world’s total carbon emissions, demonstrated significant economic growth over the past decade. Despite reducing its carbon intensity by 36%, its overall emissions increased due to rising GDP. Similar patterns were seen in India and Russia, where emissions exceeded projected goals.

Raftery pointed out the stark contrast in carbon intensity between nations, noting that China’s emissions intensity is three times higher than that of Germany, the largest economy in the European Union. The United States, which has also seen fluctuations in its commitment to the Paris Agreement, has a carbon intensity that is 50% higher than Germany’s.

The implications of this research extend to global policy discussions, particularly as nations reevaluate their commitments to emission reductions. The potential impact of the United States’ policies on global warming was also examined. If the U.S. were to withdraw from the agreement again, the overall projected temperature increase might rise by 0.1 degrees Celsius, decreasing the chance of staying below 2 degrees from 34% to 27%.

Raftery emphasized the need for more substantial efforts to counterbalance economic growth with emission reductions. “There need to be bigger efforts made to offset economic growth, but there is reason for hope,” he stated, highlighting the ongoing commitment from many nations to pursue more aggressive climate action.

This study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, provides a comprehensive analysis of the progress made under the Paris Agreement while calling attention to the urgent need for enhanced global cooperation and ambition in addressing climate change. As countries reflect on their contributions, the necessity for a collective approach to sustainability remains paramount.