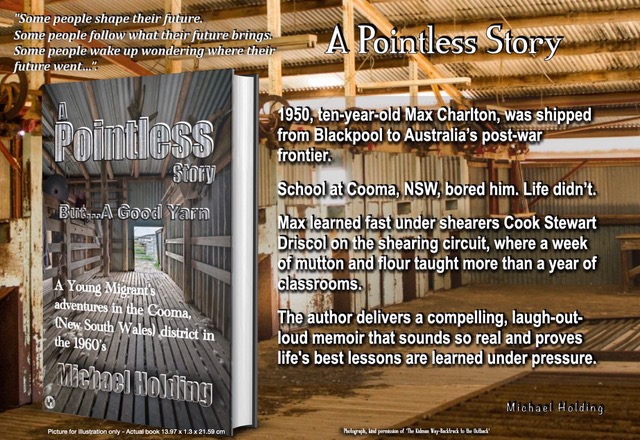

URGENT UPDATE: A glimpse into the demanding life of a shearers’ cook in Australia has just surfaced, revealing the relentless daily routine that keeps sheep shearers fueled during grueling workdays. Michael Holding’s vivid account transports readers back to the 1950s and 1960s, where the cook played a pivotal role in the harsh Australian outback, managing cooking duties while ensuring the welfare of the shearers.

From the crack of dawn, at 4:00 a.m., the day begins with a wake-up call from Stew, a seasoned cook known for his relentless work ethic. The kitchen transforms into a battlefield, with pots clanging and the smell of sizzling meat filling the air as Stew prepares breakfast for up to twenty hungry shearers. In a world where culinary qualifications are nonexistent, these cooks rely on raw skill — from slaughtering sheep to baking fresh bread.

By 5:30 a.m., the shearers stumble in, half-awake and ravenous, devouring breakfast as if their lives depend on it. The intensity doesn’t wane as the day progresses; the cooks are tasked with maintaining a steady supply of food to keep the teams energized. As the day unfolds, the realities of the job become clear: it’s a relentless cycle of cooking, cleaning, and preparing meals that stretch throughout the day.

During the lunch rush, the pressure mounts. By 12:30 p.m., the cooks are not only managing meals but are also responsible for butchering lambs, a task that requires skill and precision. The emotional toll of handling animals adds another layer to their demanding job, showcasing the psychological strength required in this profession.

Seamlessly transitioning into the dinner prep by 2:30 p.m., the pace quickens. The cooks must slice and dice, often while juggling multiple tasks at once. As the evening approaches, the shearers return for dinner, bringing with them a lively atmosphere that temporarily masks the exhaustion felt in the kitchen.

The end of the day doesn’t signal a break. By 7:00 p.m., the second round of washing up begins, and the cooks are left with towering piles of dishes to conquer. Their commitment to the job is unwavering, and by 8:30 p.m., they collapse into bed, knowing that the cycle will begin again at dawn.

Holding emphasizes the significant impact of these cooks, who earned between £30 and £40 per week, a competitive wage for the time. Their reputation was everything; a good cook could elevate morale, while a bad one could lead to strikes or even the abandonment of the job.

This revealing account highlights the vital role of shearers’ cooks, who are not just culinary experts but also the backbone of the shearing teams. Their hard work and dedication often go unnoticed, yet they are essential in keeping the operation running smoothly.

As this story gains traction, it serves as a reminder of the unsung heroes behind the scenes. Readers are encouraged to share this insight into the past and appreciate the rigorous lives led by those who cook for a living in the unforgiving Australian outback.