Recent research has revealed that breastfeeding women possess protective immune cells that may guard against breast cancer. The study, published in the prestigious journal Nature, sheds light on a long-speculated link between breastfeeding and reduced breast cancer risk, confirming theories that date back to the 18th century when physicians noted unusually high breast cancer rates among nuns.

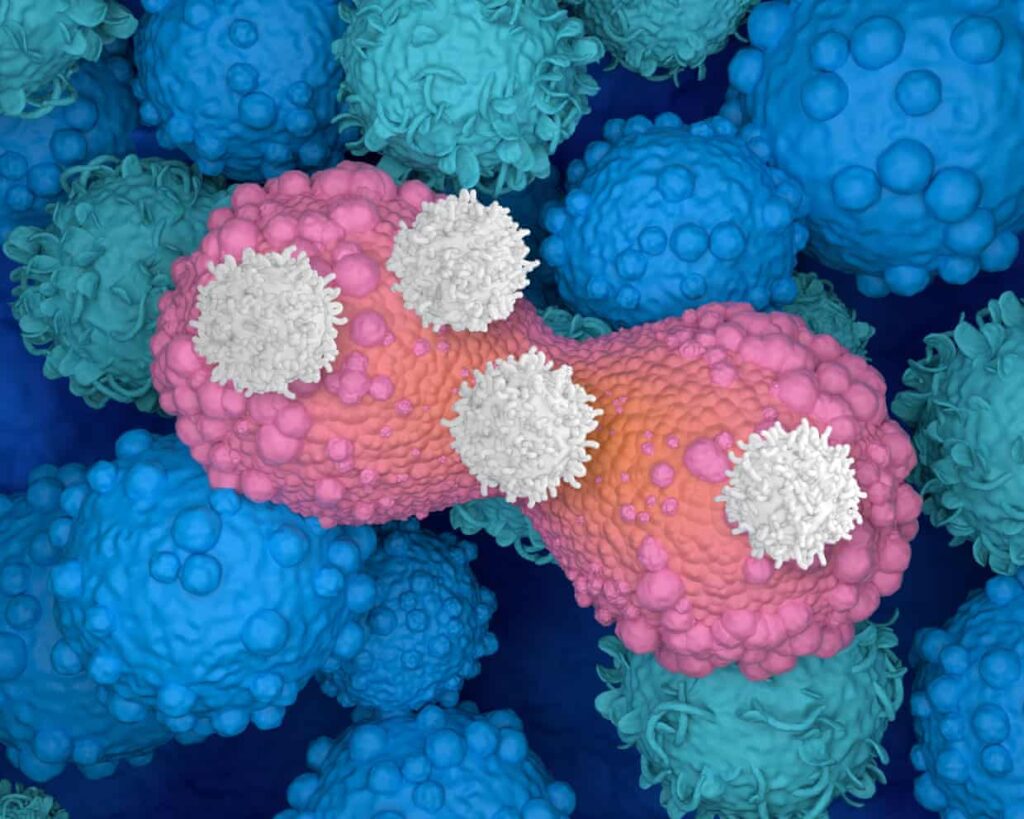

Researchers led by Prof Sherene Loi, a clinician scientist at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, examined the role of the adaptive immune system in providing protection against cancer. This system produces specialized T-cells that respond not only to pathogens but also to cancerous cells. The findings suggest that these immune cells, particularly CD8+ T-cells, play a vital role in improving patient outcomes, especially among those diagnosed with aggressive forms of breast cancer, such as triple-negative breast cancer.

The study focused on the non-cancerous breast tissue of over 260 women from diverse backgrounds, who underwent breast reduction or surgeries aimed at lowering their breast cancer risk. The research team discovered that women who had given birth exhibited significantly higher levels of CD8+ T-cells in their breast tissue. Remarkably, these immune cells persisted for more than 30 years following pregnancy.

In an experimental component, researchers utilized mouse models to observe the impact of these T-cells on cancer growth. When cancerous cells were implanted into the breast tissue of mice that had given birth and breastfed, tumor growth was notably reduced compared to virgin mice. When the T-cells were depleted in the breastfeeding mice, this protective effect diminished, indicating a direct link between T-cells and breast cancer defense.

To assess the long-term implications of breastfeeding on cancer survival rates, the researchers analyzed data from over 1,000 breast cancer patients diagnosed after childbirth. Their findings revealed that those who had breastfed exhibited improved outcomes and a higher concentration of immune cells within their tumors, suggesting ongoing immune activation against cancer.

Prof Loi emphasized the significance of these findings, stating, “The key take-home messages are that pregnancy and breastfeeding will leave behind long-lived protective immune cells in the breast and the body. These cells help to reduce risk and improve defense against breast cancer, particularly triple-negative breast cancer, but potentially other cancers as well.”

Additionally, she noted that while breastfeeding can enhance immune protection, it does not eliminate the risk of breast cancer entirely. “The effects are quite small for every individual, but population-wide, the effects are large,” she added.

Associate Professor Wendy Ingman from the University of Adelaide’s Medical School highlighted another crucial aspect of the research. She indicated that the duration of breastfeeding correlates with increased benefits. Specifically, for each additional year of breastfeeding, there is a 4% lifetime reduction in a mother’s risk of developing breast cancer.

This research not only clarifies the mechanisms by which breastfeeding may confer protection but also opens new avenues for potential therapeutic strategies. Prof Loi expressed hope that understanding these biological processes could lead to innovative vaccines and methods to simulate this protective effect in women who are unable to breastfeed or have not had children.

In summary, this study marks a significant advancement in our understanding of the relationship between breastfeeding and breast cancer prevention, reinforcing the importance of maternal health during and after pregnancy.