Australia has entered a controversial new offshore agreement with Nauru, promising over $400 million in exchange for accepting non-citizens with criminal histories—known as the NZYQ cohort. This arrangement has raised significant concerns regarding transparency, particularly as the details surrounding the deal remain largely undisclosed.

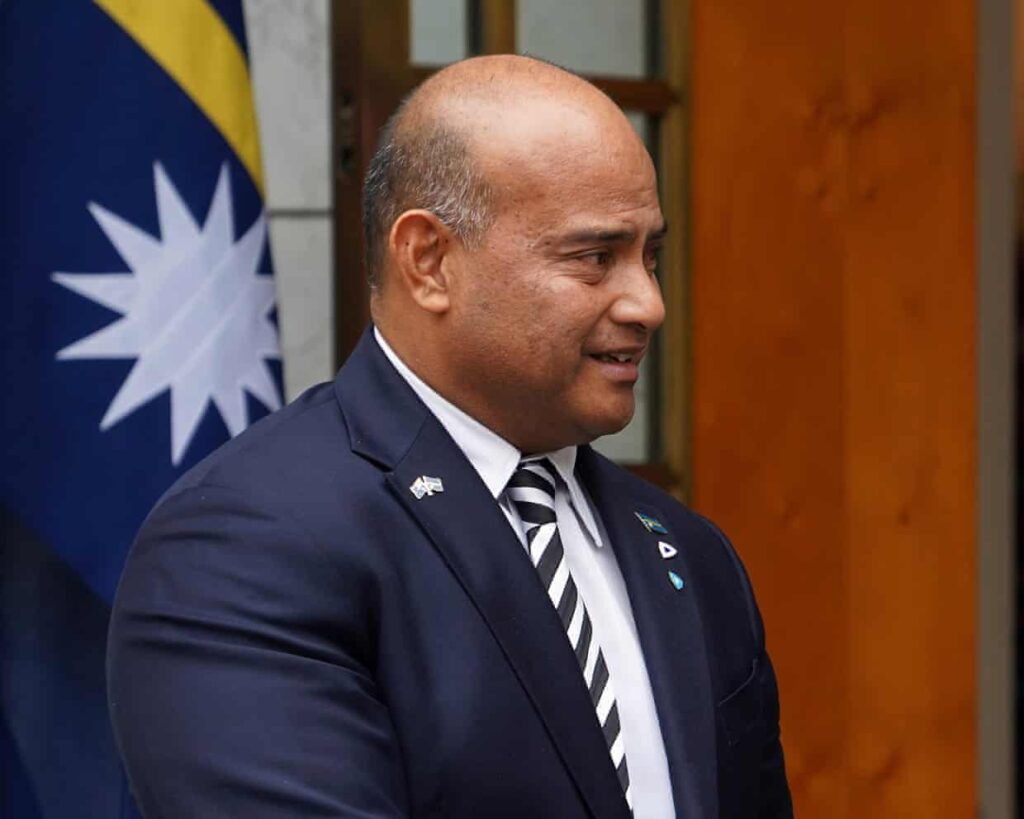

The deal, brokered in February, allows for the transfer of individuals who have completed their sentences in Australian prisons. The Nauruan president, David Adeang, explained in an interview that these individuals would be allowed to live and work in Nauru. He emphasized that they are not Australian citizens and cannot return to their home countries. “Australia is trying to send them back to their country but they are not wanted back home,” Adeang stated.

Nauru is a small island nation with a population of around 12,000, and it has a history of resettling migrants. Adeang assured that those relocated would receive 30-year visas and be subject to Nauruan laws. Despite these assertions, the conditions within the RPC3 detention centre—where at least four individuals have been forcibly sent—remain a mystery, contributing to the growing concerns about the implications of this offshore policy.

The government of Nauru has not provided an official translation of Adeang’s remarks, despite the Australian government reportedly possessing one. When the Australian Senate requested this translation, Penny Wong, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, refused to release it, citing potential harm to Australia’s international relations with Nauru. Wong noted that disclosing even parts of the information would be contrary to public interest, reinforcing a pattern of secrecy surrounding Australia’s offshore detention practices.

The Australian government has faced criticism from various quarters, with human rights organizations and think tanks labeling it the “most secretive democracy on Earth.” This characterization stems from a long-standing culture of opacity surrounding immigration policies. Past administrations have implemented strict measures to limit media access to immigration detention facilities and have often denied requests for transparency regarding bilateral agreements.

The Albanese government has similarly resisted calls to release details of its memorandum of understanding with Nauru, justifying its stance by claiming it lacks consent from the Nauruan government. Furthermore, the government has maintained confidentiality surrounding a multimillion-dollar agreement with Papua New Guinea concerning the detention of asylum seekers previously held on Manus Island.

Journalists have encountered difficulties in investigating these policies. Reports have emerged of increased restrictions on media access, including instances where journalists have been warned against interviewing asylum seekers in detention. This raises critical questions about accountability and the government’s commitment to transparency.

The ongoing secrecy around Australia’s offshore processing regime has prompted calls for greater scrutiny. If the government’s actions are indeed justifiable, critics argue, then there should be no reason to withhold information from the public. The interview conducted by President Adeang remains available online, yet the government’s refusal to disclose its translation only fuels speculation and concern over the integrity of its offshore policies.

As Australia continues to navigate its complex relationship with Nauru and its broader immigration strategy, the need for transparency and accountability remains paramount. The implications of this arrangement extend beyond borders, affecting not just the individuals involved but also the Australian public, who fund these controversial policies.