Negotiators at the COP30 climate conference in Belém, Brazil, were unable to finalize an agreement that included crucial references to transitioning away from fossil fuels as the event concluded. The negotiations extended late into the final night, ultimately resulting in no consensus among participating nations. As the clock struck midnight, representatives were informed that discussions had stalled, leaving many to return to their hotels without a resolution.

Inside the Hangar Convention Centre, government officials, researchers, and activists gathered in anticipation. According to Arthur Wyns, a research fellow at the University of Melbourne and advisor to the COP28 presidency, the atmosphere reflected the lengthy negotiations. “People were hanging out on chairs, and there were negotiators having a beer in the corner,” he noted. The tension escalated significantly after Brazil released a draft agreement that diverged sharply from previous proposals, omitting explicit references to fossil fuels and deforestation.

The urgency surrounding this year’s conference is heightened, as the world surpasses the threshold of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. A significant divide emerged between oil-rich nations, including those from the Middle East and Russia, and a coalition of around 80 countries advocating for an energy transition. Unless a resolution is reached soon, there is a risk of no agreement being established.

The controversy began early Friday morning when Brazil’s draft wording surprised many delegates. The previous draft had suggested three distinct pathways for nations to reduce their dependence on coal, oil, and gas, which account for approximately 68 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, as reported by the United Nations. Wyns remarked, “A lot of parties were quite surprised,” indicating the unexpected nature of Brazil’s position.

European Union Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra firmly stated that the EU would reject any agreement that omitted fossil fuels. He emphasized the need for a genuine transition from fossil fuels to clean energy, insisting that this shift be reflected in the final document. Similarly, negotiator Juan Carlos Monterrey from Panama warned that neglecting to address the root causes of the climate crisis could diminish the credibility of the talks. “Failing to name the causes of the climate crisis is not a compromise. It is denial,” he stated.

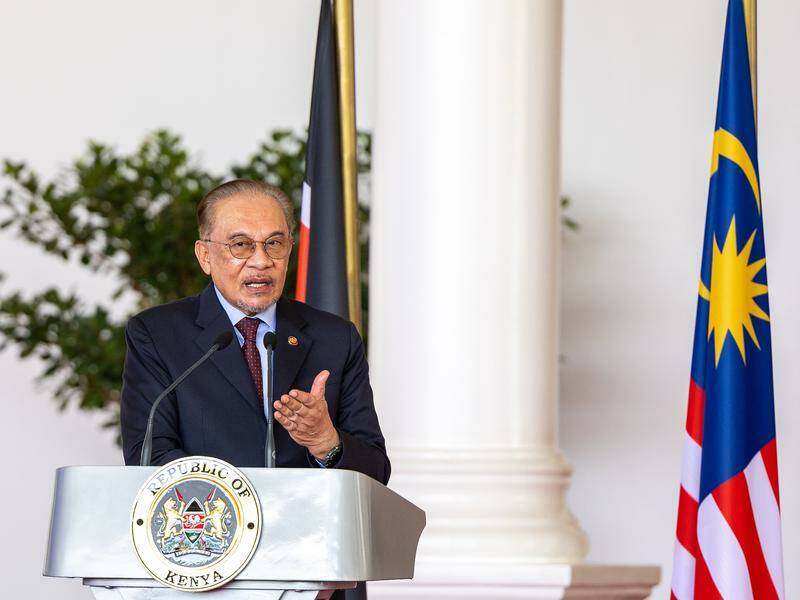

Australia, alongside the EU and the UK, is one of the nations pushing for the inclusion of fossil fuel transition plans. The country recently signed the Belém Declaration on the Transition Away from Fossil Fuels, which acknowledges the necessity of phasing out fossil fuels expeditiously. Dr. Simon Bradshaw, COP31 lead at Greenpeace Australia, praised this move as a significant commitment to limit global warming. “This is the strongest ever statement from Australia on fossil fuels, and we intend to hold them to it,” he remarked.

The COP28 conference in Dubai in 2023 was notable for including an agreement on transitioning away from fossil fuels, a landmark recognition of their role in climate change. Nonetheless, it fell short of advocating for a complete phase-out. Wyns pointed out that achieving that wording required extensive diplomatic efforts in the United Arab Emirates.

This year, the principal opposition to fossil fuel inclusion stems from the Arab group, which includes 22 member countries such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia, alongside Russia. Reports indicate that Saudi Arabia, during closed-door discussions, declared its energy industries as off-limits in negotiations.

The significance of COP30 also lies in its role as a test of international collaboration in the face of climate change, particularly with notable absences from leaders such as those from China, the United States, and India. Wyns cautioned that a failure to name fossil fuels in the agreement could signify a substantial setback for global climate efforts. “If they walk away, it could be seen or construed as a failure of multi-lateralism or a failure of the Paris Agreement process,” he added.

Looking ahead, the dynamics of the upcoming COP31, set to take place in March 2024 in Türkiye, raise concerns about the effectiveness of negotiations. Wyns highlighted the potential for a “diplomatic trainwreck,” given the differing priorities between Australia and Türkiye regarding climate change. Under a preliminary agreement, Türkiye will preside over the conference, while Australia will take on a leading role in negotiations. The document outlines that if disagreements arise, both nations will consult until a consensus is achieved.

Climate and Energy Minister Chris Bowen emphasized that the agreement between Australia and Türkiye represents a “significant concession” for both parties. “It would be great if Australia could have it all, but we can’t have it all,” he remarked, recognizing the complexities of global climate negotiations.

As the world awaits the next steps, the outcome of COP30 raises critical questions about international commitment to addressing climate change and the future of fossil fuel reliance.