NASA has achieved a remarkable milestone with the Parker Solar Probe (PSP), capturing the closest images of the Sun to date. Launched in 2018, the spacecraft is designed to explore the Sun’s outer atmosphere, known as the corona, and its magnetic field. On December 24, 2024, the PSP reached a breathtaking distance of just 6.1 million km (approximately 3.8 million miles) from the solar surface, setting a new record for proximity to the Sun.

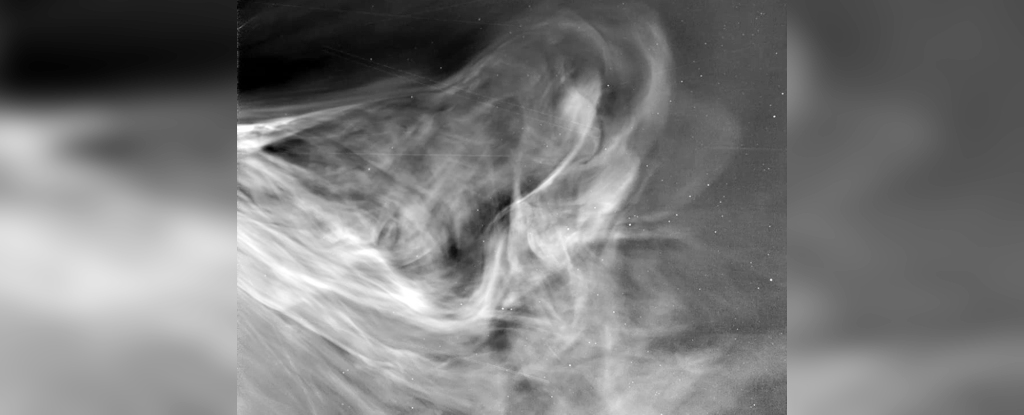

The Parker Solar Probe is not only the closest spacecraft to the Sun but also the fastest, achieving speeds of 692,000 km/h (around 430,000 mph) during its latest flyby. Equipped with advanced instruments, including the Wide-field Imager for Solar Probe (WISPR), the PSP provides unprecedented insights into solar phenomena. WISPR’s two radiation-hardened cameras allow it to image the solar corona and solar wind, presenting data in ways never seen before.

New Insights into Solar Activity

According to Nicky Fox, Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters, these latest findings transport researchers into the dynamic atmosphere of our closest star. “We are witnessing where space weather threats to Earth begin, with our eyes, not just with models,” Fox stated. This new data promises to enhance our predictions of space weather, ensuring the safety of astronauts and protecting technology on Earth and beyond.

Understanding the solar wind and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) is crucial for mitigating their effects on our planet. The solar wind is a continuous stream of charged particles that emanates from the Sun, creating beautiful auroras while also posing risks to power grids and satellites. CMEs, on the other hand, are sporadic bursts of plasma that can disrupt technological systems when they reach Earth.

The Parker Solar Probe, named after American heliophysicist Eugene Parker, who first proposed the existence of the solar wind in 1958, builds on decades of solar research. While previous missions have provided valuable insights, none have approached the Sun as closely as the PSP, leveraging cutting-edge technology to deliver critical data.

Unraveling Solar Mysteries

One of the intriguing discoveries made by the Parker Solar Probe is the phenomenon of “switchbacks.” These are zig-zagging magnetic fields observed in the solar wind, which differ significantly from the more uniform flow detected near Earth. The PSP’s observations reveal that switchbacks are more prevalent than previously thought and tend to occur in clusters. This data points to specific regions on the Sun where these magnetic funnels form, contributing to the fast solar wind—a component of the solar wind that poses various challenges for space exploration.

Understanding the dynamics of solar wind, particularly the slower variant, remains a significant challenge for scientists. The slow solar wind is denser than its faster counterpart and contributes to conditions on Earth that can rival those created by CMEs. As explained by Nour Rawafi, project scientist for the Parker Solar Probe at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, deciphering how the solar wind escapes the Sun’s gravitational pull is key to comprehending its behavior.

Looking ahead, the Parker Solar Probe’s next perihelion is scheduled for September 2025, when it will again journey through the solar corona. This upcoming flyby is expected to yield even more detailed data about the slow solar wind and other solar phenomena, along with breathtaking new images.

The ongoing research facilitated by the Parker Solar Probe continues to redefine our understanding of the Sun, its influence on the solar system, and the potential hazards posed to Earth. As we delve deeper into these solar mysteries, scientists aim to unlock answers to questions that have puzzled researchers for decades.