Researchers at the University of Sydney have successfully created cosmic dust in a laboratory setting, a breakthrough that may provide insights into the origins of life on Earth. Led by Linda Losurdo, a PhD candidate in materials and plasma physics, this innovative approach involves simulating cosmic conditions to replicate the dust that originates from dying stars.

Cosmic dust plays a critical role in understanding how life began. Each year, thousands of tonnes of this material enter Earth’s atmosphere, often vaporizing before reaching the surface. The fragments that survive—known as meteorites and micrometeorites—offer valuable clues about the cosmos. As such, scientists have employed various methods to gather these materials, including vacuum technology to collect microscopic particles from cathedral roofs.

Creating Cosmic Dust in the Lab

Losurdo’s research focuses on the chemical composition of cosmic dust, which is thought to contain essential organic compounds known as CHON molecules. These molecules, composed of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, are considered the building blocks of life. The study aims to clarify whether these molecules formed on Earth, were delivered by space debris, or emerged during the early formation of the solar system.

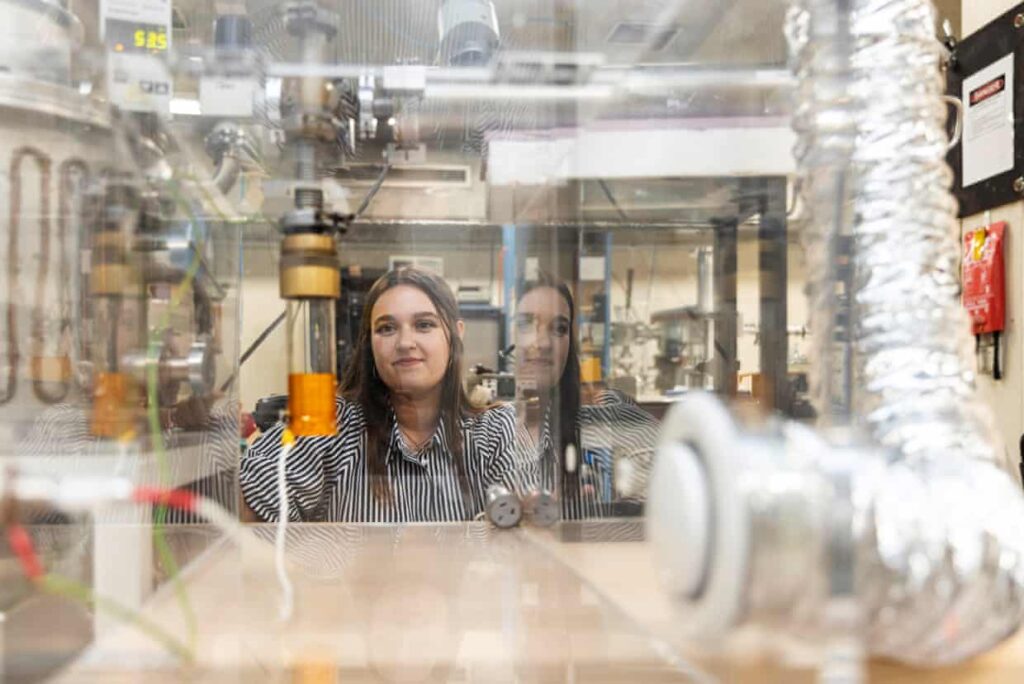

To create cosmic dust, Losurdo and her supervisor, Prof David McKenzie, utilized a glass tube to mimic the near-empty conditions of space. They introduced a mixture of gases—nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and acetylene—similar to those found around dying stars. By applying a high voltage of approximately 10,000 volts, they generated plasma, which acted as a dust analogue. Losurdo explained, “That is our dust analogue,” emphasizing the importance of this method in studying the origins of organic matter in meteorites.

Implications for Astrobiology

The research has garnered attention from experts in the field. Dr Sara Webb, an astrophysicist at Swinburne University, commented on the significance of Losurdo’s work, stating, “All of these types of dust particles were the building blocks for our life here on Earth. We wouldn’t be here without them.” Webb noted the challenges of directly acquiring interstellar dust, making Losurdo’s laboratory methods particularly valuable.

Losurdo’s team aims to use their simulated cosmic dust in future experiments to explore early life formation on various planets. While she acknowledged that their creation does not represent every environment in the universe, she emphasized that it provides a “snapshot of something that is physically plausible.”

The findings from this research are set to be published in the Astrophysical Journal of the American Astronomical Society, marking a significant step in understanding the complex processes that may have contributed to the emergence of life on Earth. This work not only sheds light on our own planet’s history but also opens avenues for exploring the potential for life elsewhere in the universe.