New archaeological findings reveal shocking evidence of cannibalism among humans living on the Iberian Peninsula during the late Neolithic period. At least 11 individuals, including children and adolescents, appear to have been skinned, defleshed, and consumed by other members of their community. This grim discovery was made in the El Mirador cave located in the Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain, and dates back to approximately 5,709–5,573 years ago.

The analysis of bones found at the site indicates that the cannibalistic acts were not part of a habitual practice but rather a singular, perhaps isolated, event. This suggests that the community may have resorted to cannibalism due to extreme social tensions, possibly stemming from conflicts between local clans.

Details of the Findings

According to paleoecologist Palmira Saladié from the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES), interpreting cannibalism is complex. In her words, “Cannibalism is one of the most complex behaviors to interpret, due to the inherent difficulty of understanding the act of humans consuming other humans.” Saladié emphasizes that societal biases often label such acts as barbaric, but the evidence points to a more intricate context.

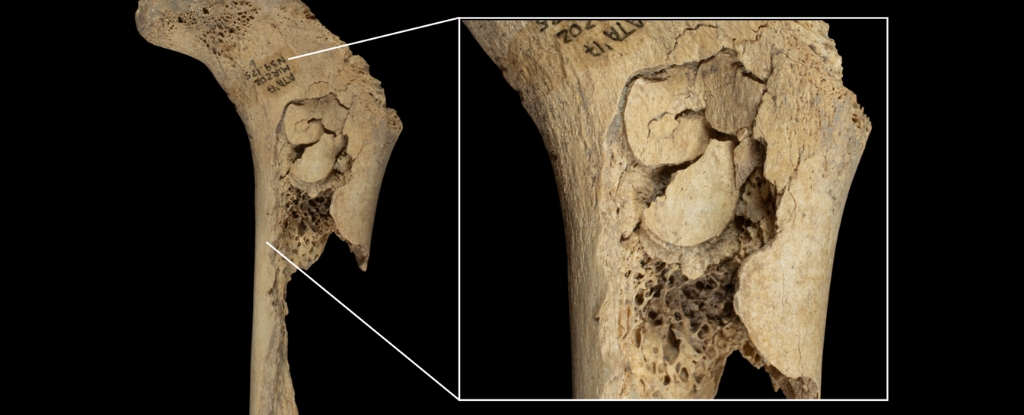

The researchers documented 650 individual fragments of human bones exhibiting signs of post-mortem processing. This includes alterations such as ‘pot-polishing’, which refers to the smoothing of bone ends consistent with being cooked, and discoloration indicative of cremation. Cut marks on 132 bones suggest various forms of dismemberment and evisceration. Some bones even displayed signs of having been gnawed by human teeth, indicating direct consumption.

Radiocarbon dating reveals that all the individuals consumed were likely killed and processed in a brief, concentrated event, potentially spanning several days. Analysis of the strontium isotope ratios in the bones confirmed that the victims were local inhabitants, reinforcing the idea that this was an act of violence rather than a funerary practice or a response to famine.

Context and Implications

The implications of these findings are significant. Francesc Marginedas, an evolutionary anthropologist and quaternary archaeologist at IPHES, states, “This was neither a funerary tradition nor a response to extreme famine. The evidence points to a violent episode, given how quickly it all took place – possibly the result of conflict between neighboring farming communities.”

This discovery contributes to a growing body of research indicating that inter-group violence was prevalent on the Iberian Peninsula during the Neolithic, likely driven by competition for resources and population pressures as communities expanded. The evidence of cannibalism serves as a stark reminder of the extreme measures societies may resort to in times of conflict.

Archaeozoologist Antonio Rodríguez-Hidalgo further notes, “Conflict and the development of strategies to manage and prevent it are part of human nature.” Historical records indicate that even in smaller, less stratified societies, violent episodes can lead to extreme measures such as cannibalism.

The findings from El Mirador cave provide a vital perspective on prehistoric human behavior and the complex relationship with death and the human body within those communities. As Palmira Saladié concludes, “The recurrence of these practices at different moments in recent prehistory makes El Mirador a key site for understanding prehistoric human cannibalism and its relationship to death.”

This research has been published in the journal Scientific Reports, adding to the ongoing dialogue about the nature of early human societies and their social dynamics.