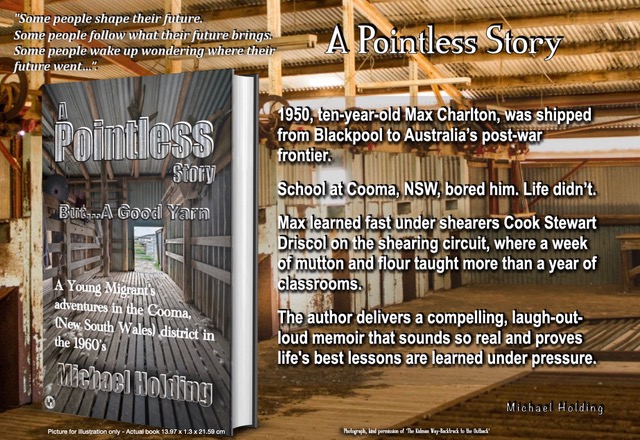

The role of a shearer’s cook in the 1950s and 1960s was pivotal, demanding a unique set of skills that surpassed the traditional culinary arts. According to Michael Holding in his book A Pointless Story, these cooks were the backbone of shearing operations, managing to keep teams of men well-fed and motivated, often without formal training or culinary qualifications.

Mastering the Craft

A shearer’s cook was not merely responsible for preparing meals; he was a multifaceted professional who combined the roles of butcher, baker, and even psychologist. Every day began at 4:00 a.m., with the cook lighting a fire to prepare breakfast by 5:30 a.m.. This meal typically included hearty options like eggs, chops, and porridge, designed to fuel the shearers for their physically demanding work.

The skills required extended far beyond cooking. Cooks had to handle livestock, often slaughtering sheep or cattle, ensuring the meat was processed efficiently and humanely. This task necessitated proficiency with both a rifle and a knife, as well as a deep understanding of butchering techniques.

In addition to meat preparation, they were responsible for baking fresh bread, scones, and pies, often using challenging wood-fired ovens. The ability to manage heat and bake effectively in adverse conditions was crucial for success. Every morning, the cook would produce enough food to feed up to twenty men, planning meals carefully to make the most of available supplies.

The Daily Grind

The daily routine of a shearer’s cook was relentless. After breakfast, which was consumed in silence by the shearers, the cook faced a mountain of dishes and the need to prepare for the next meal. Mid-morning snacks, known as crib or smoko, had to be packed and sent to the men working in the shearing shed. By midday, the cook often found himself back in the slaughter yard, ready to deal with any livestock that needed processing.

As the day progressed, the cook would pivot to lunch and dinner preparations, which were substantial meals designed to replenish the energy expended by the shearers. The camaraderie and banter that filled the dining area during these meals stood in stark contrast to the early morning silence.

Despite the demanding nature of the work, a skilled cook could earn between £30 to £40 per week, matching the pay of the best shearers. This income was stable, unlike the shearers, who faced fluctuations based on weather conditions and work availability. Payments were typically collected collectively from the shearers’ earnings, with about ten percent of each man’s pay going to the cook.

While financial compensation was significant, a cook’s reputation was paramount. A well-regarded cook could maintain high morale among the shearers, while a poor one risked mutiny or a walkout. As Holding describes, the cook’s ability to keep the team content and well-fed made him invaluable.

By the end of their long days, cooks like Stew and his assistant, Charlton, often found themselves exhausted but fulfilled. The respect earned from hard-working shearers was hard-won and deeply valued. In the world of shearing, where physical labor was the norm, the cook emerged as a vital force, blending artistry, skill, and resilience into a demanding role that kept the operation running smoothly.

The legacy of the shearer’s cook remains a testament to the essential, yet often overlooked, roles that contribute to the success of agricultural life. As Michael Holding captures in his narrative, these cooks were indeed the unsung heroes of the shearing world.