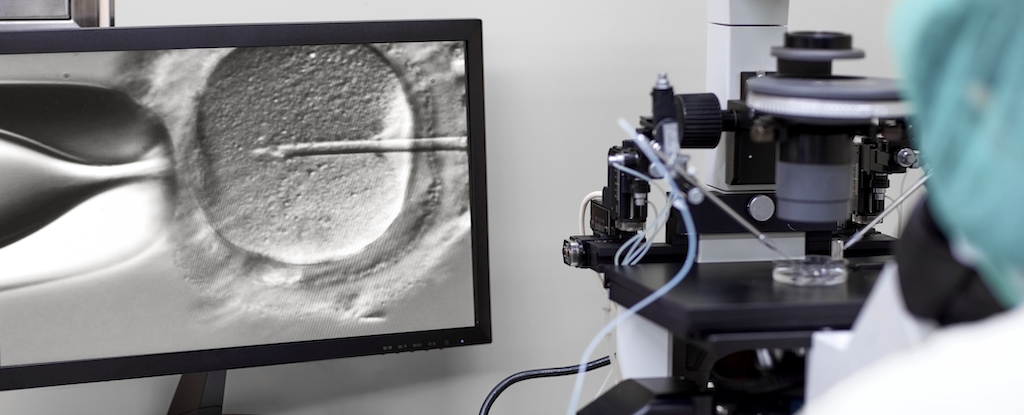

A baby born in the United States has gained international attention after arriving from an embryo that had been frozen for over 30 years. This remarkable event marks a new world record, as the embryo was created in 1994, during a time when technology was vastly different from today. Now, decades later, this frozen embryo has become a living child, raising important questions about the future of fertility treatment and the implications of long-term embryo storage.

Freezing embryos is a standard procedure in in vitro fertilization (IVF), where multiple eggs are fertilised, and any unused embryos can be preserved for future use. Each year, thousands of embryos are placed in long-term storage globally, as demand for fertility treatments continues to rise. However, the fate of these unused embryos often becomes complex once treatment concludes. Families may face changing circumstances, such as relationship breakdowns or shifts in personal wishes, leading to difficult decisions about the future of the embryos.

One option for individuals with unused embryos is donation, typically coordinated through a fertility clinic. In this groundbreaking case, the embryos were donated via a US-based Christian organisation called Snowflakes. The donor, a woman now in her 60s, expressed a desire to have a say in where her embryos were sent, given that any resulting children would be full genetic siblings to her 30-year-old daughter.

As laws vary globally, the US has no legal limits on how long embryos can be stored, unlike the UK, where the maximum period is now 55 years. This opens a possibility for children to be conceived from embryos frozen for decades, with the donor potentially being elderly or even deceased by the time of contact. This raises intriguing questions about how the age differences between donor and child, or among donor-conceived siblings, may affect their relationships.

With direct-to-consumer DNA testing on the rise, many donor-conceived individuals are increasingly seeking genetic relatives through platforms like 23andMe and Ancestry.com. These services allow users to upload DNA samples and receive lists of potential relatives, including donors and donor siblings. As the trend of longer embryo storage continues, it is likely that individuals will use these tools to connect with genetic relatives from years past, often bypassing formal donor registries.

The globalisation of fertility treatment further complicates the situation. Many individuals seeking fertility services travel internationally, leading to genetic connections spanning multiple countries. A 2024 documentary on sperm donation highlighted such complexities, showcasing how one donor fathered children across various nations, prompting discussions about the need for improved regulation of international donor practices.

The unique experience of being born from an embryo frozen for decades poses profound questions about identity and belonging. Research indicates that donor-conceived families generally function well, but individuals born from embryos created before the digital age might grapple with a unique temporal disconnect. This situation may influence their understanding of family connections and identity, especially as they learn about their genetic background and the age of their donors or siblings.

As advancements in reproductive technology continue to evolve, it is likely that this record-breaking case will not remain an isolated incident. The changing landscape of family and parenthood raises further inquiries about genetics, identity, and what it truly means to be part of a family.

Nicky Hudson, a Professor of Medical Sociology at De Montfort University, has emphasized the importance of exploring these dynamics as the implications of long-term embryo storage and donor conception become more relevant in our increasingly interconnected world.