Research at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) is delving into the world of archaea, microorganisms that thrive in extreme environments and offer insights into evolution and adaptability. These tiny organisms, often overlooked, are found everywhere—from human skin to the deepest parts of the ocean. EMBL scientists are now using advanced technologies to study archaea, aiming to unravel their potential roles in environmental recovery and their evolutionary significance.

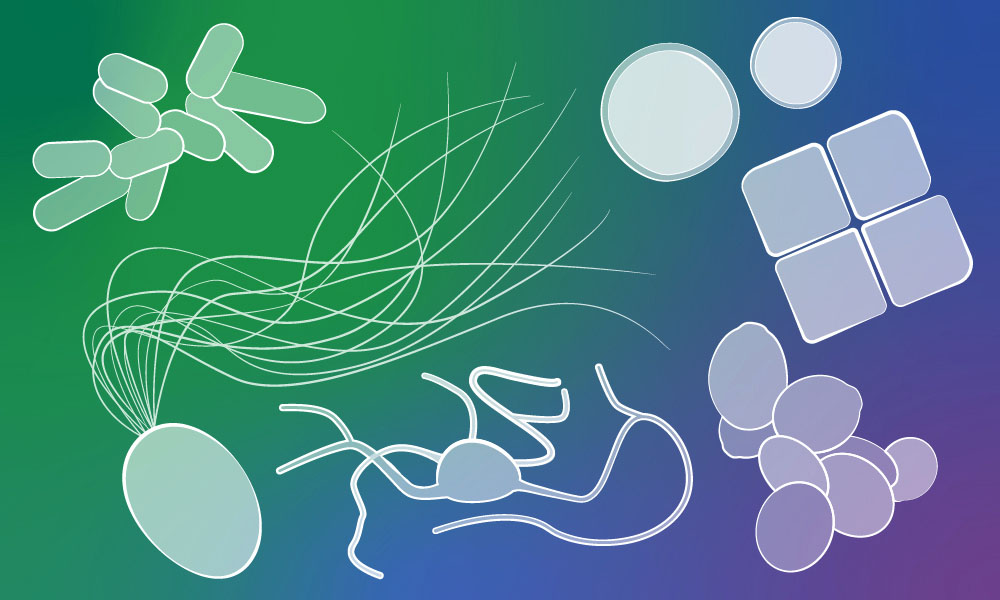

Archaea were once classified as bacteria until microbiologist Carl Woese identified their unique ribosomal RNA in the 1970s, establishing them as a distinct domain of life. Often residing in harsh conditions like deep-sea hydrothermal vents and Arctic tundra, archaea are now recognized for their resilience and ecological importance.

Investigating Asgard Archaea

One of the latest developments at EMBL involves Florian Wollweber, who recently joined EMBL Grenoble as a group leader. His research focuses on Asgard archaea, a group closely related to eukaryotes. Utilizing techniques such as cryo-electron tomography, Wollweber’s team has discovered that these slow-growing organisms possess complex cell shapes and eukaryote-like internal structures. This suggests that certain features of eukaryotic cells may have evolved much earlier than previously thought.

Wollweber’s ongoing research aims to reconstruct the evolutionary events leading to the origin of eukaryotes, shedding light on fundamental biological processes. Recent advances in microscopy and omics technologies have opened new avenues for studying these organisms, allowing scientists to uncover significant insights hidden within their intricate biology.

Archaea in Environmental Recovery

Another critical aspect of archaea research at EMBL involves their potential application in bioremediation. Kiley Seitz, a soil microbiologist in Peer Bork‘s research group, emphasizes the non-pathogenic nature of archaea, making them a promising alternative to bacteria and fungi in environmental recovery efforts. Seitz’s interest in archaea began in her youth, and she now aims to compare healthy and unhealthy ecosystems to determine the role of archaea in environmental resilience.

Through metagenomics, Seitz is sequencing entire microbial communities to identify archaeal genes and pathways. She highlights the ongoing discovery of new archaeal species and the need for more comprehensive descriptions of these organisms. In collaboration with EMBL’s TREC expedition, Seitz has been sampling soil, sediment, and water along European coasts, studying how archaea adapt to changing environments.

Archaea’s metabolic flexibility makes them ideal candidates for restoring damaged ecosystems. Their communal living patterns also pose interesting challenges for researchers, as studying them in isolation can be problematic. Seitz notes that healthier human skin tends to host more archaea, which play a role in removing ammonia and adding nitrates, further illustrating their beneficial interactions.

Understanding DNA Evolution through Archaea

Research on archaea also extends to understanding DNA evolution. Svetlana Dodonova and her team at EMBL Heidelberg recently presented the first structures of Asgard archaea’s DNA packaging, known as chromatin. Their findings indicate that a specific histone from the Hodarchaeota group can form two distinct chromatin assemblies—one compact and the other more open. This discovery may have implications for understanding chromatin regulation and the evolutionary transition from archaea to more complex eukaryotic organisms.

Dodonova’s work employs cutting-edge cryo-electron microscopy to study chromatin architecture across different archaeal species, including Thermococcus kodakarensis and Haloferax volcanii. By purifying proteins and manipulating DNA structures, her group aims to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms that enable extremophiles to thrive in harsh environments.

Exploring Extremophiles in the Andes

Field research is also crucial in understanding archaea’s adaptability. Federico Vignale, a postdoctoral fellow at EMBL Hamburg, conducts research in the Central Andes of Argentina, an area characterized by extreme conditions. His team focuses on Salar de Antofalla, where they study microbial life in high-salinity lakes. Vignale notes that these conditions offer insights into early life on Earth and may inform the search for extraterrestrial life.

The research team collects samples while navigating challenging environmental conditions, including high winds and dramatic temperature fluctuations. Their studies have revealed diverse archaeal communities thriving in mineral-rich lakes, which exhibit unique pigmentation that aids in UV protection.

As Vignale’s team continues to explore these uncharted territories, they are acutely aware of the threats posed by increasing tourism and lithium mining in the region. They emphasize the importance of protecting these fragile ecosystems while conducting their research in collaboration with local communities.

The ongoing exploration of archaea at EMBL represents a significant step in understanding these remarkable microorganisms and their potential contributions to science and the environment. By uncovering the secrets of archaea, researchers hope to gain valuable insights into evolution, ecosystem health, and the origins of life.