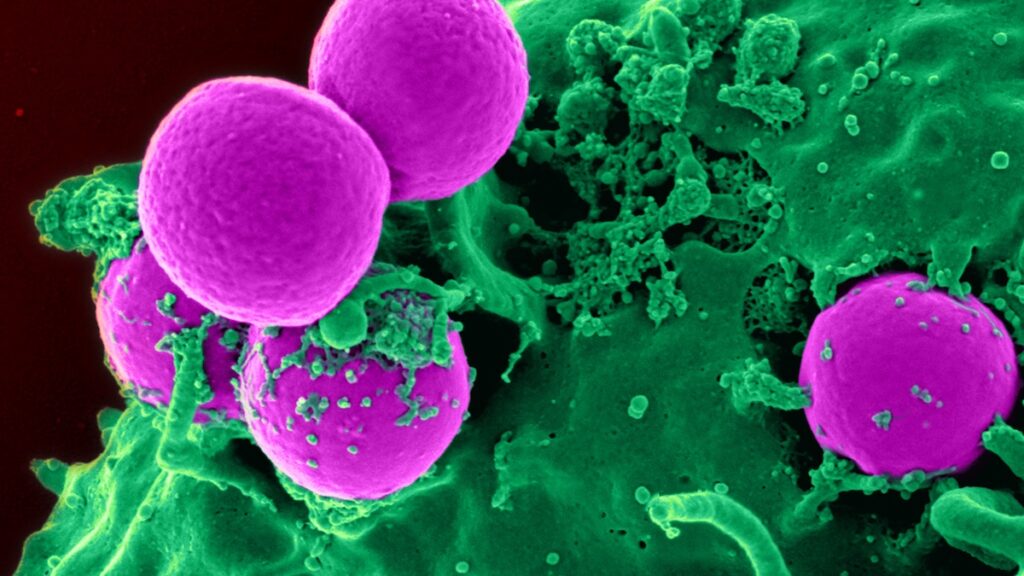

Dangerous bacteria are evolving rapidly, developing ways to evade antibiotic treatments, a phenomenon known as antimicrobial resistance (AMR). A recent study reveals concerning insights into this issue, as researchers have identified latent antimicrobial resistance in sewage systems across the globe. By examining wastewater, scientists aim to understand the future of drug-resistant microbes, which already contribute to over 1 million deaths annually.

An international team of researchers analyzed 1,240 sewage samples from 351 cities in 111 countries. They focused on antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) that grant pathogens protection against antibiotics. In addition to known ARGs, the researchers employed a method called functional metagenomics to detect latent genes—genetic variations that exist but are not actively expressed. These latent ARGs can potentially activate under certain conditions, raising concerns about their role in the evolution of drug-resistant “superbugs.”

The findings suggest that latent ARGs are more prevalent than previously understood. According to Hannah-Marie Martiny, a bioinformatician at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), “The research shows that we have a latent reservoir of antimicrobial resistance that is far more widespread around the world than we had expected.” This discovery highlights the importance of understanding how resistance genes develop, as the researchers found that selection and competition are more significant factors than dispersal in this phenomenon.

To combat future threats posed by antimicrobial resistance, the team advocates for enhanced wastewater surveillance. Co-first author Patrick Munk, an associate professor at the DTU National Food Institute, emphasizes the necessity of monitoring not only known ARGs but also latent resistance genes. Munk asserts, “To curb future antimicrobial resistance, we believe that routine surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in wastewater should encompass latent resistance genes to account for tomorrow’s problems as well.”

Traditionally, researchers have concentrated on ARGs that can be transferred between microbial species due to their immediate threat to public health. However, examining latent ARGs can yield critical insights into the origins and ecological dynamics of antimicrobial resistance. Martiny explains, “By tracking both acquired and latent antimicrobial resistance genes, we can gain a broad overview of how they develop, change hosts, and spread in our environment.”

Wastewater surveillance presents a practical and ethical approach to monitoring AMR, as it aggregates waste from humans, animals, and their surroundings. While most latent resistance genes may not pose an immediate threat, the researchers caution that some could become problematic in the future. “In general, I don’t think we need to be too worried about most latent antimicrobial resistance genes, but I do believe that some of them will eventually cause problems,” says Martiny.

Identifying which latent genes may lead to future resistance could help predict how bacteria respond to new antibiotics. Munk warns, “When new antibiotics are developed— a process that takes many years— bacteria may already have invented new ‘scissors’ capable of destroying them.” By studying both active and latent genes over time, researchers hope to determine which latent genes may transition into significant resistance threats and how they spread geographically.

The research underscores the urgency of addressing antimicrobial resistance as a global health challenge. With the potential for latent ARGs to contribute to future public health crises, this study serves as a call to action for increased awareness and proactive measures. The findings were published in the journal Nature Communications, adding to the ongoing discourse on antimicrobial resistance as an urgent global health issue.