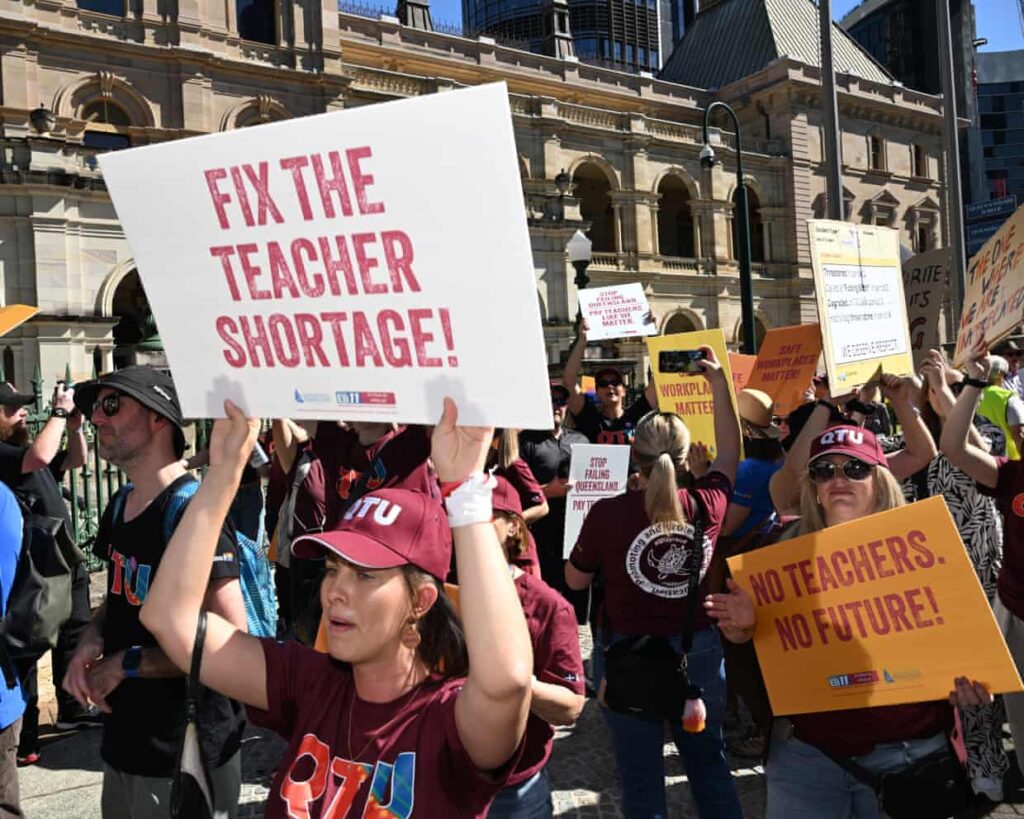

Australia is grappling with severe teacher shortages, a situation described as “diabolical” by education advocates. An international report from the OECD highlights that these shortages disproportionately affect disadvantaged and remote schools, significantly hindering educational quality across the nation.

According to the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (Talis), released this month, approximately **42%** of lower secondary school principals in Australia reported that a lack of teachers has negatively impacted instruction quality. This figure is nearly double the OECD average of **23%** and represents a significant increase from **14%** in **2018**. The crisis is particularly acute in regional and disadvantaged schools, where **63%** of principals in regional areas and **67%** in schools serving students from low socioeconomic backgrounds reported staffing issues.

Mathew Burt, principal of Broome Senior High School in Western Australia, has witnessed the impact of these shortages firsthand. Having moved to the region in **2018** from Perth, Burt noted, “You go to some metropolitan areas where you see teachers and principals that are in schools for 15 years or more. When you’ve got principals changing over every few months in some regional areas, the trust and confidence of the community in that school drops as a result.”

The convener of Save Our Schools, **Trevor Cobbold**, emphasized that the report underscores a critical staffing crisis in Australian education. “The increased shortage restricts learning in schools, especially in disadvantaged public schools,” he said, adding that this situation poses a significant barrier to closing the achievement gap between affluent and less privileged students.

The report reveals that Australian teachers are working an average of **46.5 hours** per week, well above the OECD average of **40.8 hours**. High stress levels are prevalent, with **65%** of teachers reporting stress and **80%** indicating their job adversely affects their mental health. A related study from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) found that teachers experience depression, anxiety, and stress at rates three times the national average, largely linked to overwhelming workloads.

The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership has reported that around **30%** of teachers are contemplating leaving the profession before reaching retirement age. In Western Australia alone, **1,279** teachers resigned during the **2024-25** academic year, the highest recorded since data collection began in **2005**.

Correna Haythorpe, president of the Australian Education Union, characterized the situation as “unacceptable for a wealthy, developed nation.” She noted that teacher shortages began to escalate in the last three years, coinciding with the aftermath of the pandemic. Many prospective teachers reconsidered entering the profession, while existing teachers evaluated their longevity in the field. Haythorpe attributed the ongoing crisis to a long-standing lack of resources in public education. “Teachers carry that burden because you don’t want to let any child down,” she said.

A recent report by the Australian Primary Principals Association highlighted the negative effects of teacher shortages, with some schools losing specialist subjects like music and arts and experiencing attendance declines. A principal from a regional school expressed the daily struggle, stating, “Every day starts with a spreadsheet of who’s absent and ends with wondering how much longer we can keep this up.”

In response to these challenges, education ministers agreed at the end of **2022** to implement a National Teacher Workforce Action Plan aimed at addressing shortages. The plan focuses on teacher supply, education, and retention. Since its introduction, there has been a **7%** increase in annual applications for teaching degrees, alongside announced changes to teacher training.

Some individual states have reported improvements. In New South Wales, for instance, public school vacancies have decreased by **61%** over three years, dropping from **2,460** unfilled positions in **2022** to **962** in the third term of **2025**. This decline has been largely attributed to a pay agreement secured by teachers in **2023**, making them among the highest paid in the country, along with the introduction of dedicated recruitment officers at schools.

While Haythorpe acknowledged the positive changes at the start of the recruitment pipeline, she stressed the importance of adequate funding. “It should be used to address escalating workloads and to ensure that we have more educational support personnel, allowing teachers the time to teach effectively,” she stated.

Burt also noted some minor successes, such as incentives for student teachers to complete placements in regional schools. However, he emphasized that these measures do not resolve the issue of continuity, which is vital for both student performance and community cohesion.

Looking to the future, Burt’s daughter has begun her teaching degree and is benefiting from government scholarships and paid placements. He recognizes that her career path may differ significantly from his own. “When I first came into teaching, I had to go to a country area for my first posting. My daughter will walk into a job at any one of those primary schools in the metropolitan area where she lives,” he remarked.

He concluded with a call for a comprehensive national strategy to address the teacher shortage. “Right now, we’re just pinching teachers from each other. Schools that are less desirable are ending up with worse shortages, which exacerbates the problem.”

As Australia continues to navigate this pressing educational crisis, the focus remains on finding sustainable solutions that can strengthen the teaching workforce and ensure quality education for all students, particularly those in the most vulnerable communities.