Research from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, reveals that chimpanzees demonstrate improved problem-solving abilities in larger, more cooperative groups. The study, published in *Communications Psychology*, explores how cooperation and leadership influence sustainable resource management among these primates.

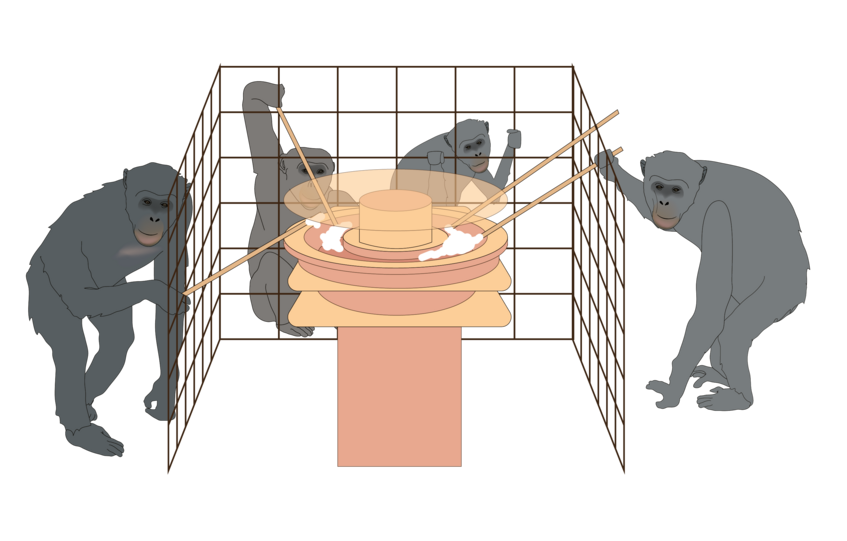

In a controlled experiment, researchers presented chimpanzees with a resource dilemma involving a bowl of yogurt. The challenge required them to balance personal gain against collective sustainability. A single stick supported the lid of the yogurt bowl, preventing it from closing and making the treat inaccessible. If left unsupported, the lid would close tightly, blocking access to the yogurt.

First author Kirsten Sutherland explained, “There was a clear conflict between feeding individually and keeping the resource available for the group.” For the chimpanzees to sustain access to the yogurt, at least one individual had to forgo eating temporarily.

To assess the impact of group size on cooperative behavior, the study involved 24 groups of chimpanzees, tested in pairs and in groups of four. Each group completed 18 test trials and 18 control trials, the latter of which had no lid and thus no dilemma. Surprisingly, pairs of chimpanzees did not perform well in resolving the dilemma, often removing all sticks quickly and making the yogurt inaccessible.

In contrast, groups of four chimpanzees exhibited significantly better cooperation, leaving at least one stick in the yogurt pool for an average of 83 seconds longer compared to pairs. “The same chimpanzees that failed to overcome the dilemma in pairs showed greater sensitivity when placed in a larger group,” noted Sutherland. This suggests that larger, more tolerant groups foster an environment where individuals modify their behavior for the benefit of the group.

The study also highlighted the role of social dynamics in cooperative success. Cooperation thrived in groups characterized by high social tolerance—where members spent time together with low aggression levels. Additionally, the resource remained accessible longer when the highest-ranked chimpanzee was the one without a stick.

Senior author Daniel Haun remarked, “This shows that dominance does not necessarily undermine cooperation. What matters is how dominant individuals use their position.” When high-ranking chimpanzees exercised restraint, the entire group benefited. Conversely, if they took more than their fair share, collective sustainability was compromised.

These findings contribute to a broader understanding of dominance, social tolerance, and prosocial behaviors in chimpanzees. The research suggests that chimpanzee groups can effectively manage resources in a sustainable manner, particularly when dominance is paired with a non-competitive attitude.

The implications extend beyond chimpanzees, offering insights into human cooperation. The study indicates that many social cognition experiments involving non-human primates may be flawed if they test individuals in pairs. “Chimpanzees are adapted for group living,” Haun emphasized. “If we want to understand their cooperative abilities, we need to study them in social contexts that reflect that reality.”

This research underscores the importance of group dynamics in sustainable cooperation, highlighting how similar principles may also apply to human societies. Understanding these parallels could inform strategies for better resource management in our own communities.