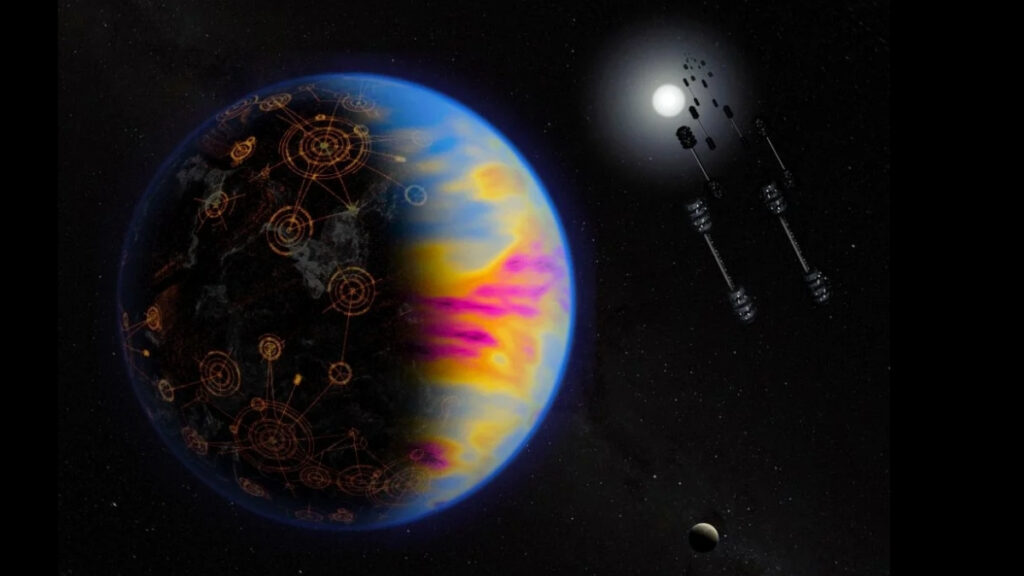

Contact with extraterrestrial intelligence may not unfold as envisioned in popular culture. Instead of invasions or benevolent saviors, researchers suggest that the first signals from alien civilizations could be strikingly loud and atypical. This insight comes from a new study by David Kipping, director of the Cool Worlds Lab at Columbia University, set to be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in March 2024.

Kipping’s paper introduces the concept known as the Eschatian Hypothesis, which posits that the initial detection of extraterrestrial technological life is likely to be an unusual and strong signal, rather than a representative one. This hypothesis draws on historical patterns observed in astronomy, where the first detected examples of various phenomena often have larger observational signatures due to the biases inherent in our detection methods.

The history of exoplanet discovery serves as a prime example. The earliest exoplanets identified in the 1990s were those orbiting pulsars, which are highly visible due to their precise timing. Currently, fewer than ten of over 6,000 exoplanets cataloged by NASA are found around pulsars, indicating that these early discoveries were not typical. Similarly, while approximately one-third of the visible stars to the naked eye are evolved giants, this does not reflect their actual population in the galaxy, but rather their brightness.

Kipping elaborates on how this phenomenon could extend to first contact with extraterrestrial intelligence. He notes that “if history is any guide, then perhaps the first signatures of extraterrestrial intelligence will too be highly atypical, ‘loud’ examples of their broader class.” He draws an analogy to supernovae, which are exceptionally bright and detectable due to their dramatic endings.

The Eschatian Hypothesis suggests that the signals we might first encounter could arise from civilizations in unstable or declining phases. Some scientists posit that human civilization’s struggles with climate change may create a detectable technosignature that could attract the attention of extraterrestrial intelligences. The famous Wow! signal, detected in 1977, is speculated by Kipping to potentially represent such a cry for help from a civilization nearing its own end.

Kipping emphasizes that the search for technosignatures should adapt to this understanding. Current research strategies should focus on detecting broad and anomalous transients, rather than narrowly defined technosignatures. He argues that observatories like the Vera Rubin Observatory and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey are crucial in this regard, as they continuously monitor the cosmos for changes and could be pivotal in identifying these atypical signals.

“The Eschatian Hypothesis provides a suggested pathway forward,” Kipping concludes. By prioritizing the detection of loud, short-lived civilizations, scientists may be better positioned to recognize the first signs of extraterrestrial life.

This perspective reshapes how humanity might envision its first encounter with alien life, moving away from dramatic and fictionalized scenarios. Instead, it underscores the likelihood that our initial contact will manifest as a strikingly loud signal, illuminating the complexities of life that may exist beyond our planet. As our exploration of the cosmos continues, the search for these unusual signals may soon reveal answers to one of humanity’s most profound questions: Are we alone in the universe?