The recent study led by the University of Washington reveals that while the Paris Agreement has facilitated some reductions in greenhouse gas emissions over the past decade, these efforts are insufficient to counterbalance the environmental impacts of economic growth. Signed by nearly 200 nations in 2015, the agreement aimed to limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, with a more ambitious target of 1.5 degrees Celsius.

A decade of data has been analyzed, demonstrating a downward trend in carbon intensity—defined as carbon emissions per unit of economic output—but overall emissions have continued to rise, primarily due to increased gross domestic product (GDP). According to Adrian Raftery, a professor emeritus of statistics and sociology at the University of Washington and lead author of the study published on October 17, 2023, “The efforts made in response to the Paris Agreement did change the course of things, but the effects were knocked out by an increase in GDP.”

The study builds on previous research, including a 2017 assessment that predicted only a 5% chance of remaining below the 2-degree warming threshold, even if all countries fulfilled their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) as outlined in the agreement. A follow-up in 2021 suggested that emission reduction targets needed to be approximately 80% more ambitious to achieve meaningful progress.

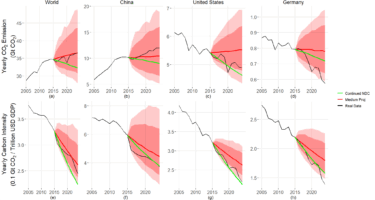

Despite a positive trend in carbon intensity, which declined by 3.1% annually since the agreement took effect, the global economy’s growth has outpaced these reductions. Raftery noted, “Even though less carbon was released to produce each economic unit, global GDP increased enough to drive total emissions up.”

The research further highlights significant disparities among countries. China, responsible for nearly one-third of global carbon emissions, experienced substantial economic growth while managing to reduce its carbon intensity by 36% by 2024. However, this reduction was overshadowed by a dramatic increase in total emissions. Similar trends were observed in India and Russia, where emissions rose significantly above their projected goals.

The implications of these findings are critical. The likelihood of experiencing severe climate events, defined as a temperature increase of 3 degrees Celsius or more, has decreased from 26% in 2015 to just 9% today. Conversely, the chance of keeping warming below 2 degrees Celsius increased from 5% to 17% during the same period.

The role of the United States in this dynamic remains significant. Following an announcement by former President Donald Trump to withdraw from the agreement, the country rejoined under President Joe Biden, who committed to a 60% reduction in emissions from peak levels by 2035. The study calculated that if the U.S. were to cease its contributions while other countries met their targets, the projected temperature increase could rise by 0.1 degrees Celsius, diminishing the likelihood of staying below 2 degrees Celsius to 27%.

Raftery emphasized the need for intensified efforts to offset economic growth, stating, “The fact that the Paris Agreement did work in reducing at least carbon intensity is good news. There need to be bigger efforts made to offset economic growth, but there is reason for hope.”

This comprehensive analysis, funded by the National Institutes of Health, underscores the complex relationship between economic growth and environmental sustainability, highlighting the need for continued commitment and innovation in climate policy.