A groundbreaking genetic test has been developed to predict which children are at the highest risk of developing a high body mass index (BMI) later in life. This innovative tool, known as a polygenic score (PGS), aims to assist parents in establishing healthier habits from an early age. The research team, comprising international experts, published their findings in the journal Nature Medicine.

The polygenic score groups various genetic variations to assess the likelihood of a child experiencing obesity in adulthood. According to genetic epidemiologist Roelof Smit from the University of Copenhagen, the power of this score lies in its ability to predict obesity risk before the age of five, well ahead of other environmental factors that influence weight later in childhood. Smit emphasized, “Intervening at this point can have a huge impact.”

While the test provides valuable insights, it is crucial to recognize that genetics accounts for only a fraction of the risk associated with high BMI. Additionally, there is an ongoing debate within the scientific community regarding the appropriateness of BMI as a measure of obesity and overall health. Nonetheless, the researchers assert that their PGS is up to twice as accurate as existing models.

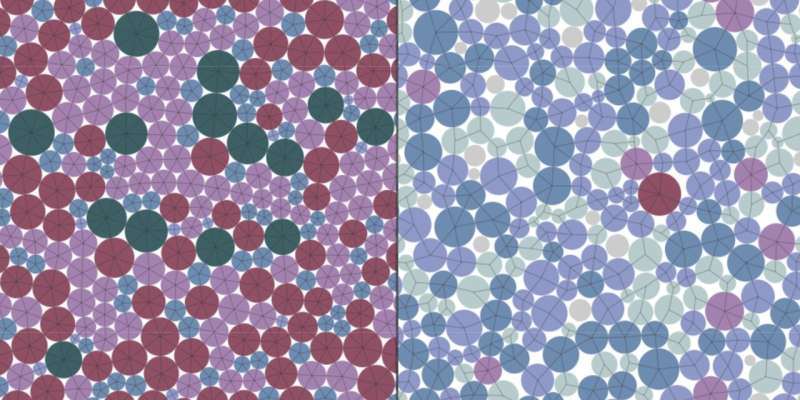

The development of this test utilized a comprehensive database of genetic information derived from over 5.1 million individuals. After creating the PGS, the researchers validated its effectiveness across multiple health databases, which included extensive records of genetic data and BMI over time. The study revealed that higher PGS scores were linked to greater weight gain in adulthood.

Key Findings and Implications

The accuracy of predicting BMI variance using the PGS varied depending on age and ancestral background. For instance, PGS scores at the age of five accounted for 35% of the BMI variation observed at age 18. In middle-aged European populations, it explained 17.6% of the variance, while the score’s effectiveness was significantly lower in other groups, such as rural Ugandans, where it accounted for only 2.2% of the variation. The researchers attribute this disparity to underrepresentation in the training data and the higher genetic diversity present in African populations.

Interestingly, the study found that individuals with a stronger genetic predisposition to higher BMI tended to lose more weight during the first year of weight loss programs, although they also faced a higher likelihood of regaining weight later on. The researchers noted, “Our findings emphasize that individuals with a high genetic predisposition to obesity may respond more to lifestyle changes and, thus, contrast with the determinist view that genetic predisposition is unmodifiable.”

The potential for early identification of obesity risk allows children and their parents a wider timeframe to cultivate healthier lifestyle choices regarding diet and physical activity. This proactive approach could significantly influence BMI outcomes throughout life.

Geneticist Ruth Loos, also from the University of Copenhagen, remarked on the advancements brought by this research, stating, “This new polygenic score is a dramatic improvement in predictive power and a leap forward in the genetic prediction of obesity risk, which brings us much closer to clinically useful genetic testing.”

The findings from this extensive study could pave the way for new strategies aimed at combating childhood obesity, offering hope for healthier futures for at-risk populations.