A groundbreaking study published in Nature Physics has reported the first experimental observation of a fragile-to-strong transition in deeply supercooled water, a phenomenon that has puzzled scientists for nearly three decades. This transition occurs when water, cooled below its freezing point without crystallization, exhibits significant changes in its viscosity and structural dynamics.

Water exhibits unique properties when cooled under conditions that prevent it from freezing. Previous research indicated that water’s viscosity would diverge to infinity at approximately 227 K (–46°C), suggesting that the movement of liquid water would come to a standstill. This prediction has long conflicted with established properties of water, leading scientists to propose that a critical transition must occur at specific low temperatures, known as the fragile-to-strong transition (FST).

Prof. Kyung Hwan Kim from the Department of Chemistry at POSTECH and Prof. Anders Nilsson from the Department of Physics at Stockholm University co-authored the study and discussed their findings. “Water is the most essential substance for life and countless natural phenomena,” Kim stated. “Understanding its anomalous properties is crucial, particularly in the deeply supercooled regime where experimental investigation has been challenging.”

Overcoming Experimental Challenges

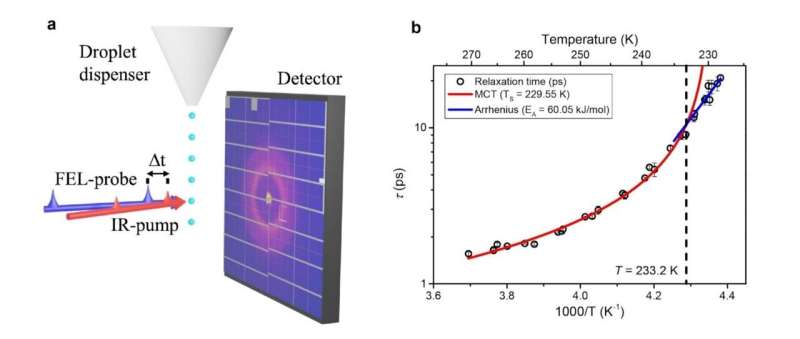

Historically, the fragile-to-strong transition had resisted direct observation due to the rapid crystallization of water below approximately 235 K. The researchers achieved a breakthrough by employing a novel droplet-based sample scheme combined with ultrafast X-ray free-electron lasers.

“We created liquid water down to –45°C by rapidly evaporating it under vacuum, allowing it to remain supercooled for only a brief moment,” Nilsson explained. The team generated micron-sized water droplets, approximately 17 μm in diameter, in a vacuum chamber. As the droplets traversed the chamber, evaporative cooling reduced their temperature to a range between 228 K and 270 K (–45°C to –3°C).

By applying a femtosecond infrared laser pulse to induce a slight temperature increase in each droplet, the researchers monitored how the liquid structure relaxed back to equilibrium. They tracked the X-ray scattering signal’s response to each temperature pulse, measuring the structural relaxation rate of water and examining whether the slowdown shifted near the proposed transition.

Tracking Structural Relaxation

Using ultrashort X-ray pulses from SwissFEL and SACLA, the team analyzed wide-angle X-ray scattering patterns at various time delays. This allowed them to directly observe how water’s hydrogen-bonding structure evolved following each temperature perturbation.

“In our experiment, we applied a small perturbation to liquid water at each temperature and then tracked the structural relaxation dynamics to a new equilibrium state over time,” Kim noted. The research captured a dynamic crossover at approximately 233 K (–40°C). Above this temperature, relaxation times increased significantly with decreasing temperature, characteristic of fragile liquids. Below 233 K, the data followed a shallower Arrhenius temperature dependence typical of strong liquids.

The findings align with molecular dynamics simulations utilizing the TIP4P/2005 water model, which replicated a similar fragile-to-strong crossover around 238.7 K. This model, which represents each water molecule with four interaction sites, offers reasonable accuracy in depicting both structural and dynamic behaviors.

“Crystallization has historically made experiments in this temperature range challenging, so much of the work has relied on computer simulations,” Kim explained. “Connecting our experimental results with molecular dynamics simulations was a crucial step.”

The observed transition temperature of approximately 233 K is slightly above the previously identified Widom line at 230 K, where fluctuations between high-density and low-density liquid configurations are most pronounced. This suggests that the fragile-to-strong transition is associated with changes in the populations of these molecular arrangements, rather than linked to the glass transition at 136 K.

Future Directions

Understanding water’s dynamics is vital not only in physics but also in various fields, including weather patterns and biological chemistry. By elucidating the mechanisms behind water’s anomalous behavior, the researchers aim to enhance our understanding of phenomena reliant on water.

“We have yet to directly observe the detailed microscopic mechanisms behind this behavior,” Kim stated. “With further advancements, it may be possible to probe these underlying mechanisms experimentally. Our method also provides an opportunity to study water below 230 K, paving the way for investigating other phenomena in this temperature range.”

This study reinforces the idea that water’s apparent divergence is interrupted by a genuine change in relaxation behavior, indicating that its dynamic anomalies are rooted in a real transition rather than an extrapolation artifact. This supports decades of theoretical and simulation work surrounding the fragile-to-strong crossover.

In summary, the research marks a significant milestone in our understanding of water’s complex behaviors and opens new avenues for future exploration.