Research published in Nature Communications reveals that human skin cells can be transformed into fertilizable eggs, marking a significant advancement in reproductive science. The study, led by Shoukhrat Mitapilov and colleagues at Oregon Health & Science University, demonstrates the potential of cell reprogramming to address infertility, a condition affecting millions globally.

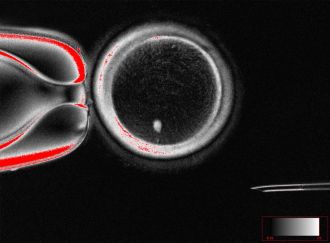

Infertility often arises from issues related to gametes, specifically the oocyte (egg) or sperm. Traditional methods like in vitro fertilization (IVF) do not always succeed, prompting researchers to explore innovative alternatives. One such method, somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), involves transferring the nucleus of a somatic cell—such as a skin cell—into a donor egg cell that has had its own nucleus removed. This allows the somatic cell to differentiate into a functional oocyte.

A notable challenge with SCNT is that the resulting cells typically contain an extra set of chromosomes, leading to potential complications during fertilization. The research team introduced a novel technique called mitomeiosis, which mimics natural cell division and discards one set of chromosomes. This process successfully produced 82 functional oocytes, which were then fertilized in laboratory conditions.

Approximately 9% of the fertilized eggs developed to the blastocyst stage by day six post-fertilization. However, the embryos did not progress beyond this point, which is critical for potential implantation in IVF treatments. The authors acknowledged limitations in their research, including the failure of many embryos to develop past fertilization and the presence of chromosomal abnormalities in some blastocysts.

Potential Impact on Infertility Treatments

The findings of this proof-of-concept study indicate that generating viable human gametes from skin cells is feasible, opening avenues for further research into reproductive technologies. Experts in the field recognize the implications of this work.

Prof. Roger Sturmey from the University of Hull highlighted the significance of understanding the molecular processes involved in chromosome segregation in eggs. He noted that creating functional egg cells from differentiated cells could reshape approaches to infertility treatment. However, he cautioned that the low success rates observed in the study mean clinical applications are still a distant prospect.

Prof. Ying Cheong from the University of Southampton emphasized the breakthrough nature of mitomeiosis. She remarked that as more people encounter challenges using their own eggs due to age or medical conditions, this research could eventually transform the landscape of infertility treatment and miscarriage prevention.

Prof. Richard Anderson, from the University of Edinburgh, reiterated the potential of generating new eggs. He indicated that the ability to create egg-like cells with the correct chromosome number could be a major advancement for women who have lost their eggs due to various reasons, including cancer treatment.

Despite the promise of these findings, the researchers stress that extensive safety evaluations and additional studies are necessary before considering clinical applications. The research underscores the importance of transparent dialogue with the public regarding advancements in reproductive science and the governance surrounding these developments.

As the scientific community continues to explore the implications of this groundbreaking research, the potential for new infertility treatments using skin cells remains an exciting frontier in reproductive medicine. Further studies will be essential to address the challenges identified and to ensure the safety and efficacy of such techniques in human applications.