Ezra Frech places two black boxes in his backpack and jumps on his electric scooter to ride a few blocks to the University of Southern California. The 19-year-old Paralympian is about to give his professors a compelling reason for missing the first three weeks of the semester. Those boxes contain the two gold medals he recently won at the 2024 Paralympics in Paris, triumphing in the 100-meter and high jump for the T63 classification.

“It’s USC; they are known for their Olympians,” says Frech, born with congenital limb differences. “I know the professors can understand the Olympics, but I wasn’t sure if they even realized the Paralympics were going on.” As Frech waits at a stoplight on Jefferson Boulevard near downtown Los Angeles, two USC students whisper, “Is that that Paralympian?” One student snaps a picture of him crossing the street.

By the time Frech arrives at the Cinematic Arts building, multiple people have stopped him for photos. “I had been recognized before Paris, a little bit, because of the Tokyo Paralympics and my social media where I posted everything from my disability to training to modeling for fashion brands, but never to this extent,” Frech says. “I couldn’t believe it, honestly. It just made me feel like, ‘Wow, this is happening. I’m here for a purpose and reason.'” Frech keeps his gold medals in his backpack for his first few weeks of school, sharing them with anyone who wants to try them on.

Breaking Barriers in Collegiate Athletics

Frech has been in the national spotlight since the 2020 Tokyo Games, where he was featured in ads from Team USA and NBC. He’s also one of the faces of the 2028 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Los Angeles, where his Angel City Sports foundation provides sports clinics and competition opportunities to people with disabilities. With a social media following of over 250,000 and celebrities such as Selena Gomez reposting his achievements, Frech gained the attention of the fashion world, modeling for designers like Hugo Boss.

Paris brought new levels of fame to Frech, who, on his way to class on this clear September day, knows he’s making history just by being on USC’s campus. As the first above-the-knee amputee to be recruited to an NCAA Division I track and field program, Frech’s goal is to show the world that an athlete with a disability can compete against the best college athletes without disabilities. He embraces the pressure of that goal with USC’s outdoor track and field season just months away.

“For me, this is life or death,” Frech says. “I believe what I do out on the track, my marks, my medals, all impact how the world views disabilities. I genuinely believe my purpose on this Earth is to normalize disability, be an example of what’s possible as an amputee.”

Overcoming Challenges and Finding a Place

High jumper Sam Grewe, now Ezra’s mentor and Team USA teammate, became the first amputee to compete in NCAA Division I track and field when he walked onto Notre Dame’s track and field program in 2019. When Frech was in high school, he realized there weren’t any adaptive programs at the colleges he wanted to attend. So he made it his goal to become the first above-the-knee athlete to be recruited to a Division I program.

“I wanted to do something no one’s ever done before,” Frech says. “Trailblazing is in my DNA. I love pursuing things that seem impossible.” Frech reached out to hundreds of NCAA coaches during his junior and senior years at Brentwood School in Los Angeles. “Our current marks to make the squad are seven meters in the long jump and 1.96 meters in the high jump,” one coach wrote to Frech. “We have some guys on the squad who are not quite at those marks yet, but they’re primarily decathletes or have other events.”

At the 2020 Tokyo Paralympics, 16-year-old Frech placed fifth in the high jump with a personal best 1.80 meters and eighth in the long jump with 5.85 meters. Shortly after, he was jumping 6.20 meters in the long jump and 1.83 meters in the high jump. Between his junior and senior years in high school, Frech raised his marks to 6.86 meters in the long jump and 1.95 meters in the high jump. In 2023, Frech set a world record and earned the gold medal in the men’s high jump T63 category with 1.95 meters at the world championship.

“I needed someone to believe in the vision,” Frech said. “Because this is the coach that I was going to be spending the most important four years of my career with. And if this coach isn’t going to believe in me when I’m on the cusp of accomplishing a specific mark, then how am I going to sit here with this coach and say, ‘I want to win three gold medals in L.A. in 2028 at the Paralympics’?”

The inquiries and rejections went on for nearly six months. Then, in summer of 2023, he heard from USC’s newly hired jumping coach, Jeff Petersmeyer. “The first time I saw him jump, he just kept making bars,” Petersmeyer said. “He just kept making bars, and I was really impressed. And I was like, ‘Man, this guy’s got some potential.’ You could be the highest high jumper, the further long jumper, but if it’s not a good match, then you’re probably not the right person for us here at USC.”

By December, USC had offered Frech admission to the university with “the understanding that you will compete as a member of USC’s Men’s Track and Field team during at least your first year of enrollment at the university.” Ezra also received the inaugural Swim With Mike Foundation’s Amir Ekbatani Paralympic Scholarship, awarded to a Paralympian attending USC or UCLA.

A Legacy of Inspiration and Determination

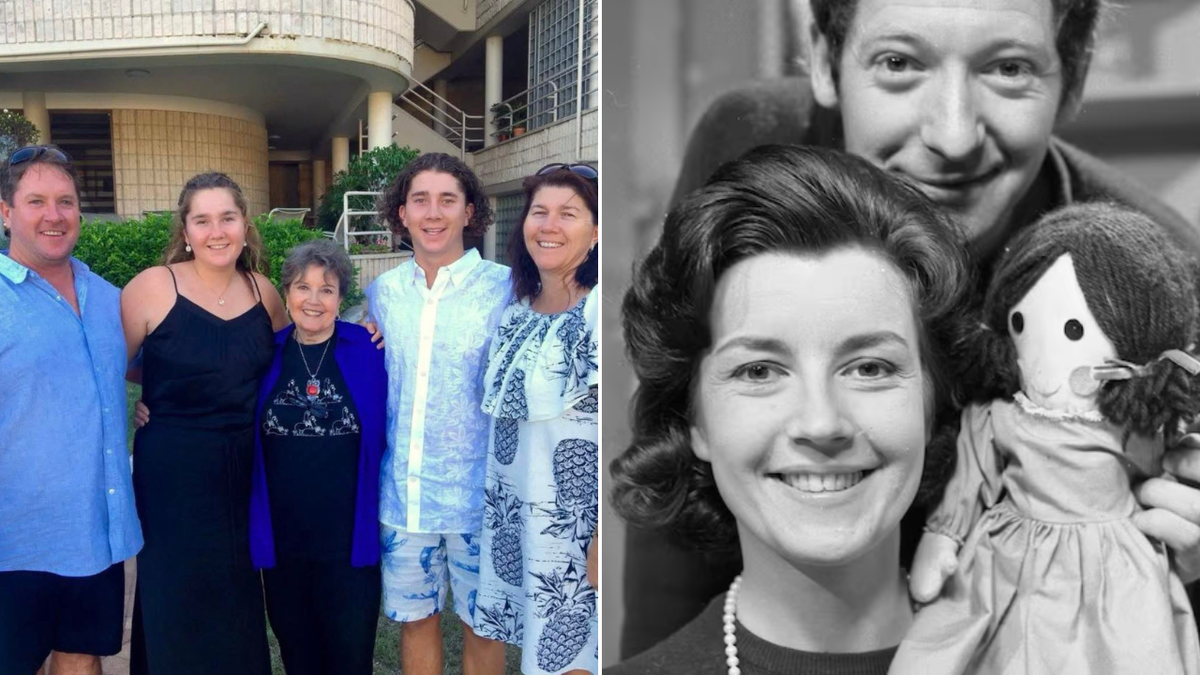

On May 11, 2005, Bahar Soomekh lay in the hospital bed at Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles, her newborn son wrapped in a blanket in her arms. She wasn’t aware of the pandemonium happening around her in the delivery room. Bahar and Clayton were told their son was born with congenital limb differences—a condition where the limbs do not fully develop or form while the baby is in the womb.

Physically, the newborn didn’t have a left knee, left fibula, or four fingers on his left hand. His left leg was curved up toward his waist, and his left arm and hand were curled toward his chest. Despite numerous tests and 3D ultrasounds during the pregnancy, doctors missed the signs of a congenital condition. Less than 24 hours later, doctors told the new parents that their son’s leg would have to be amputated and discussed options for surgeries that would provide mobility on his left hand.

At 2 years old, Frech underwent groundbreaking surgery to amputate his left leg and transplant his left big toe to his left hand. Frech’s surgeons at Boston Children’s Hospital pioneered the procedure with the goal of improving hand function and allowing engagement in physical activities. While his parents made a point of never hiding his disabilities, as he grew older, Frech began to realize how his body was different from those of other people he saw.

When he was 4, the year he got his first prosthetic leg, Frech was staring at himself in the bathroom mirror at his home in Brentwood, tears streaming down his face. He called to his mother. “Who looks like this, Mom? Who? No one is like me,” Frech sobbed. “Why did God pick me to not have the leg? Why did God pick me not to have the fingers?”

“Look at me,” she told him. “Remember your name. Ezra, which means to help, which means to teach. Your purpose is to help and teach the world about the beauty of disability. God picked you because you’re going to change the world.”

By his 10th birthday, sports had become a huge part of that life. “When I was playing a sport, I wasn’t thinking about the fact that I was the only person at my school with a disability,” he says. “I was just one of the athletes.”

Looking Forward: Challenges and Aspirations

Playing on a club basketball team, Frech practiced a few times a week with his teammates and coaches. But he would dedicate time in his backyard, before and after school, to honing his skills, dribbling the basketball between his right leg and left prosthetic, navigating his own mobility on the court. At practice and on game days, Frech displayed unwavering confidence. But as his skills developed, so did the disparaging comments.

“Underestimating me probably pisses me off the most,” Frech says. “I always had to go the extra length to prove my worth, because it was so unlikely that the kid with the disability was going to be a starter on the team.”

Frech’s journey is far from over. As he prepares for the 2025 World Para Athletics Championships, he’s not shy about his goals for his next season with the Trojans. “I will make the Big 12 team. I will travel to more away meets. And I will continue to improve my skills and develop. It wasn’t expected that I would come out and win everything in college. This is new territory. But I’m here,” Frech says.

Through his journey, Frech continues to inspire others, including young athletes like Nathan Kuhn, who sees Frech as a role model. “I just wanted to be like him,” says Kuhn, now 12. “I watched videos of him jumping over the bar, and I thought if he could do it, then maybe I could try it too. It was the first time I ever saw anyone that looked like me do something like that.”

As Frech competes and trains, he remains a beacon of hope and possibility for athletes with disabilities, proving that with determination and resilience, barriers can be broken and new paths forged.