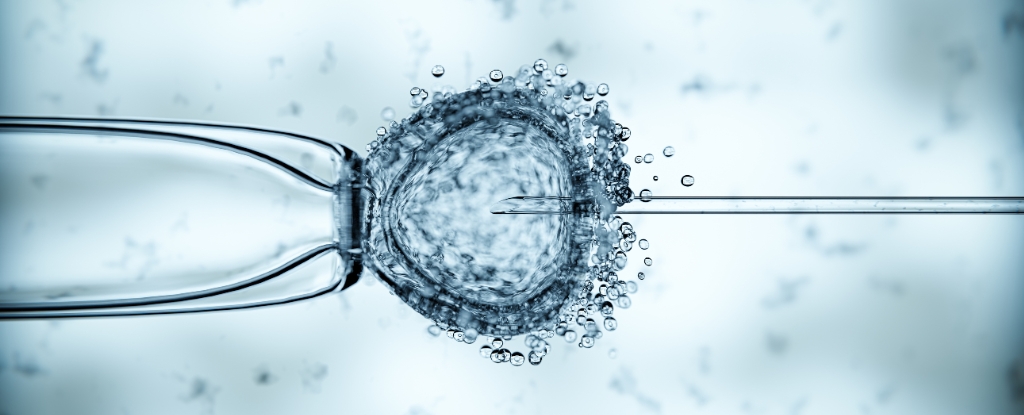

Eight healthy babies have been born in the United Kingdom using a groundbreaking in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) technique, marking a significant advancement in reproductive medicine. This world-first trial has demonstrated the potential to reduce the risk of mothers passing on debilitating genetic diseases linked to mitochondrial DNA.

The results of this innovative approach were published in several studies in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 15, 2024. This technique utilizes a small amount of healthy mitochondrial DNA from a donor egg, combined with the mother’s egg and father’s sperm. It represents a pivotal moment for women with mitochondrial mutations, offering the possibility of having children free from serious inherited conditions.

Breakthrough Results and Health Monitoring

Out of 22 women who participated in the trial at the Newcastle Fertility Centre in northeast England, eight babies were born—four boys and four girls—ranging in age from under six months to over two years. Researchers found that the amount of mutated mitochondrial DNA associated with disease was reduced by 95-100 percent in six of the babies. For the other two, the reduction fell between 77-88 percent, which is considered below the threshold that typically leads to disease manifestation.

These outcomes indicate that the technique has been effective in minimizing the transmission of mitochondrial diseases from mother to child. Currently, all eight infants are healthy, although one experienced a temporary heart rhythm disturbance that was successfully treated. Researchers plan to continue monitoring their health over the coming years to identify any potential issues that may arise.

Nils-Goran Larsson, a Swedish reproductive expert not involved in the study, described the findings as a “breakthrough,” highlighting the technique as a “very important reproductive option” for families impacted by severe mitochondrial diseases.

Ethical Considerations and Global Context

Despite its promise, mitochondrial donation remains a contentious topic and has not been approved in numerous countries, including the United States and France. Some religious leaders and ethicists have expressed concerns regarding the destruction of human embryos involved in the process. Critics also worry that this technique could lead to the advent of genetically engineered “designer babies.”

An ethical review conducted by the UK’s independent Nuffield Council on Bioethics played a crucial role in enabling this research, according to the council’s director, Danielle Hamm. Furthermore, Peter Thompson, head of the UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, emphasized that only individuals with a “very high risk” of transmitting mitochondrial diseases would qualify for this treatment.

Concerns have also been voiced regarding the application of mitochondrial donation for infertility in other countries, such as Greece and Ukraine. French mitochondrial disease specialist Julie Stefann remarked that while the benefits for those with mitochondrial diseases are apparent, the advantages in infertility cases remain unproven.

Dagan Wells, a reproductive genetics expert at Oxford University, noted that while the study’s findings are promising, some in the scientific community may feel that the limited number of births—only eight children—does not fully reflect the extensive time and effort invested in the research.

Among the children being closely observed, three have exhibited signs of a phenomenon known as “reversal.” This occurs when a treatment initially succeeds in producing an embryo with low levels of defective mitochondria, but the proportion of abnormal mitochondria increases significantly by the time the child is born. Understanding and addressing this reversal remains a challenge for researchers.

As this groundbreaking technique continues to evolve, the implications for reproductive health and genetic disease prevention are substantial, sparking both excitement and ethical debate in the medical community.